Welcome to the Forecaster's Corner.

This is a place where Flathead Avalanche Forecasters and other avalanche professionals will contribute thoughts and musings on the current avalanche situation or avalanche stuff in general. Send us a note and tell us what you think at [email protected].

Post #22 - 10/5/22

FOFAC Leadership Updates

With gratitude and appreciation, we say goodbye to three longtime board members: Dow Powell, Becky Smith-Powell, and Roland Frey.

"It's hard to overstate the impact of their tireless effort on avalanche safety in Northwest Montana. Where we are today has a lot to do with these three. Thank you so much, Becky, Dow, and Roland!" FOFAC Executive Director Emily Struss says. "We have a great team coming on board for the next chapter of FOFAC, but they have big shoes to fill."

As sad as we are to see them go, we are thrilled to announce Ted Steiner as President and Zak Anderson as Secretary of the FOFAC community Board of Directors.

Zak Anderson's family moved to Whitefish in the winter of 1990 after falling in love with skiing at Big Mountain. As a youth Zak became an avid skier and an athlete on the local ski racing team. Zak is a University of Montana graduate with work experience in real estate development, marketing, sales and public relations. After pursuing a career that took him to Phoenix, New York, and San Francisco Zak returned to the Flathead Valley to be closer to family and the recreational activities he is passionate about (skiing!). He worked for the Flathead Valley Ski Education Foundation for more than 10 years serving as assistant coach whilst bartending at nights at the Whitefish Lake Golf Club and Abruzzo Italian Kitchen to make ends meet. Zak has volunteer experience from his time as a member of the Whitefish City-County Planning Board and the Whitefish Visitors & Convention Bureau; serving as Chairman for 4 years. Zak now lives in Coram with his family where he is the General Manager of Green Valley Ranch.

Ted Steiner lives in Whitefish with his wife, Lisa and son, Ruedi. He has been based out of Whitefish since the early 80s and although he has left for seasons at a time, this is his home and he considers himself so fortunate to be part of this community.

Beginning in the mid 80s through early 90s he began pursuing a profession in snow safety, learning winter rescue skills as a volunteer with the Flathead Nordic Ski Patrol and working as a ski patroller at the Big Mountain Resort. In 1998 Ted obtained a BA degree in Physical Geography with a minor in Hydrology in 1998 from Montana State. Following graduation from MSU, he decided to continue working in the avalanche safety arena, ski patrolling in Utah and transitioning back home, to the Valley, where he was hired as the Executive Director (ED) for the Friends of the Glacier Country Avalanche Center (GCAC). GCAC, for those that may not realize, was the precursor to what is now the Flathead Avalanche Center. It was in existence for 17 years from 1995 to 2012. Ted worked with GCAC as the ED starting in 2001 and eventually moved to a new position, Education Director, as demand for avalanche safety courses in the Valley increased.

In 2005, he stepped down from his position at GCAC to start working with David Hamre as an avalanche safety specialist. His focus back then was to assist Hamre and BNSF Railway management in starting an avalanche safety program for Railway ops in JFS Canyon. Establishing the Railway avalanche program was successful endeavor and, now, 17 years later he continues to work with Hamre and provide avalanche safety assistance to the Railway. Whew!

"I’m so excited to be getting involved once again with the non-profit leadership side of FOFAC. Thank you to all on the FOFAC Executive Committee and Board for having confidence in me to assist FOFAC and our community," Ted says.

It'll be hard for all of us to say goodbye to Becky and Dow! Luckily they will stick around as FOFAC board alum. It's hard to overstate the impact their tireless effort has has on our organization's rebirth almost a decade ago, during the transition from GCAC to FAC.

""Safe backcountry travel to all!" Becky and Dow say. "Developing and crafting FOFAC from a group of dedicated backcountry users to a fully functioning organization with over $100,000 annual operating budget has been an exciting and rewarding experience. We’ve proud to have been part of FOFAC’s awesome group of board members.

Post #20 - 2/11/21

Season Update, chapter 2

By Mark Dundas, FAC forecaster

Chapter 1 of our season ended as an Atmospheric River entered the forecast region on January 12th. Earlier weather events advertised as rivers underperformed and resembled streams, creeks, or even babbling brooks. However, this one was a game-changer. It arrived as an old school Pineapple Express with over 2 inches of water, freezing levels to 7000 feet, and wind gusts that reached 100 mph. The danger rose to HIGH, and we issued an Avalanche Warning for all zones. A widespread avalanche cycle ensued, with large dry slab avalanches occurring during the early part of the storm before temperatures rose and precipitation transitioned to rain. Impressive piles of dry and wet debris reached valley floors in many locations, with at least two large slides impacting a popular groomed snowmobile trail in Canyon Creek. Debris piles were up to D3 in size, large enough to destroy a wood frame house.

This storm’s lasting impact was a widespread surface crust found on all aspects and elevations throughout the area. Interestingly, due to orographic lifting, the crust generally increased in thickness with elevation.

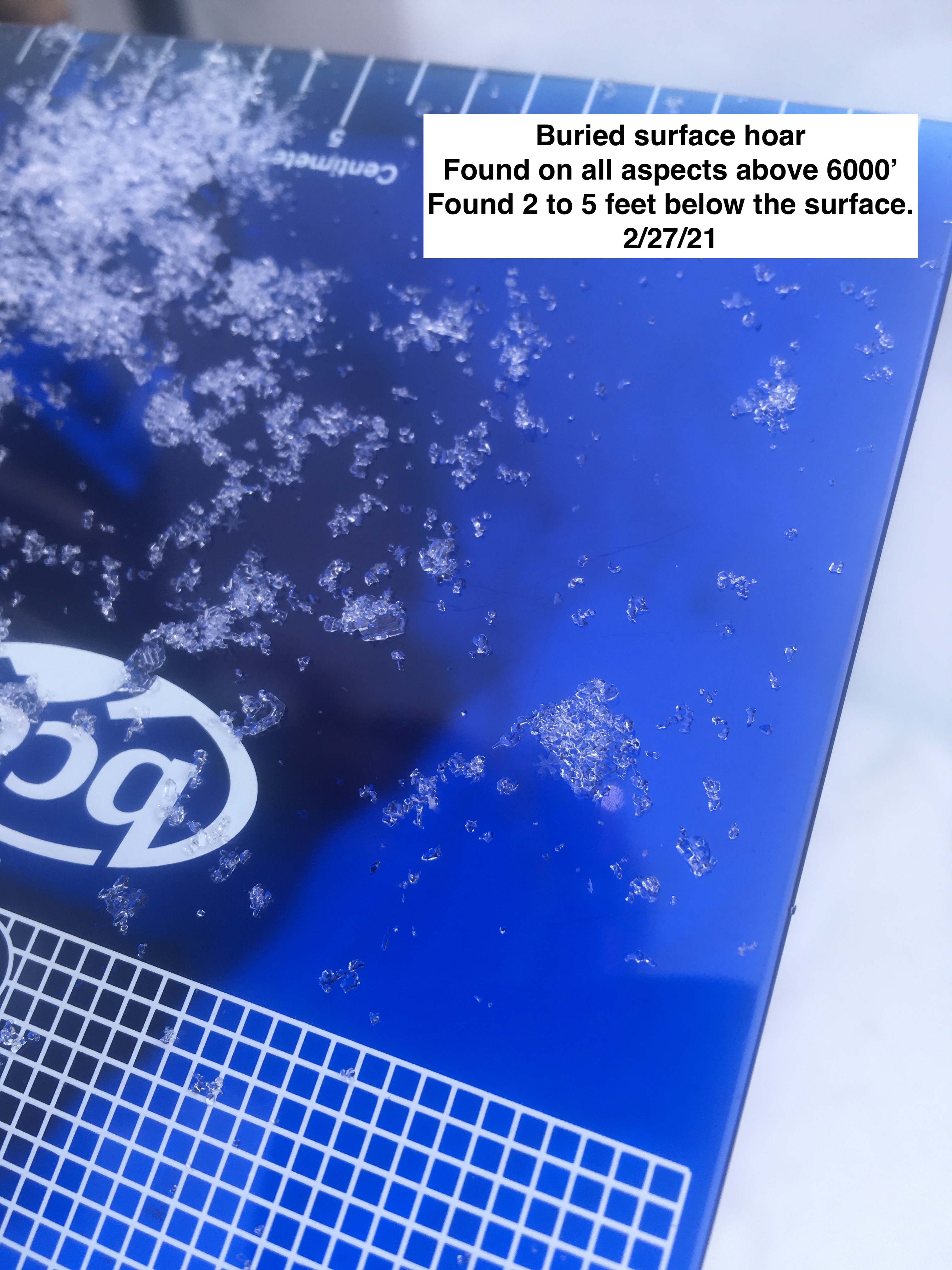

Post-Pineapple Express, most of our area experienced a drought that lasted nearly two weeks. The exception was a quick-hitting disturbance that impacted the Swan Range with 1.1 inch of water and 8 inches of snow in a 7-hour window ( Noisy Basin SNOTEL). An observer noted a natural storm slab cycle with 4-6 inch crowns on top of the 1/13 crust. Otherwise, we experienced cold, clear nights, mild weather, and seven consecutive days where we rated the avalanche danger LOW. Riding was sporty, as we learned to navigate an unforgiving crust. The calm weather resulted in a variable snow surface of either a widespread layer of surface hoar or facet development above the crust. Dribs and drabs of snowfall characterized this period, burying weak layers under a few inches of snow.

Substantial snowfall returned in late January and lasted into early February. It dramatically improved the riding but elevated the avalanche danger. The danger rose to HIGH February 4th - 8th in the Swan and the Flathead zones, and February 7th - 8th for the Whitefish zone. Reports of intentionally-, remotely-, and accidentally-triggered avalanches continued for nine consecutive days through February 6th. Most of these failed in the weak layers above the 1/13 crust. Slides ran far and fast on top of the slick crust. Riders reported several close calls, including separate incidents where a skier and snowmobiler were caught and carried. Unfortunately, a snowmobile fatality occurred on February 6th in Wounded Buck Creek in the Swan Range. Preliminary reports indicate an avalanche hit the whole party of 5, one of whom did not survive.

On Super Bowl Sunday, a cold arctic air mass spilled over the Continental Divide resulting in frigid air temperatures, breezy north and east winds, and dry conditions. The deep freeze was long-lasting, five days and **counting as of the publishing of this post. The cold temperatures and partly cloudy conditions lead to surface hoar development and faceting in the near-surface snowpack. Yet another weak layer to track when the storms return. The bitterly cold weather inhibits the strengthening of buried weak layers and keeps the Persistent Slab as a lingering problem going forward.

Despite what appears to be a relatively dry season, the Flathead River Basin reports 99% average SWE on February 11th, with Flattop in central GNP leading the charge with 113%. Noisy Basin in the Swan Range weighs in at 106%, and even a low-elevation site, Emery Creek, reports near average SWE. Perhaps not the La Nina year we hoped for, but still better than most across the western U.S.

Post #19 - 1/30/21

Old dogs, new tricks: Community-Building Communication (part 1)

By blase reardon, FAC Director

Two recent backcountry encounters have prompted me to think more about an avalanche safety tool that doesn’t get much mention in classes, forecasts, or research.

*****************

The cold week before Christmas, a friend and I met at WMR to catch an early chair, for a longer tour in the backcountry adjacent to the resort. We converged on the Canyon Creek notch with several other parties on a similar schedule. It had snowed six inches or so of low-density fluff overnight. Nobody wasted much time getting skins on and getting up the ridge. While I saw pom-pom hats, bed-head hair, and a week’s worth of beard stubble, the moment had a serious feel, like a Monday-morning commute.

At the summit of Skook, a young gun approached as we transitioned, made eye contact, and nodded as he skinned along the ridge.

“Morning,” he said. “You headed out north today?”

“Yeah.”

Well-used and not recently-washed gear. A beard that had struggled a month to look a week old. And bed head. I was envious, not having enough hair anymore for bed head.

“Great. We’re going to Oz, then back up, maybe down Dorothy’s.”

My partner and I nodded.

“Two more somewhere behind me,” he continued. “We’re all on 4-20.”

It took me a minute. Do people announce their wake-n-bakes now? Oh, 4-20 was their radio channel and privacy code.

“You guys got radios?”

I didn’t; it was my day off.

“I do,” my partner replied. I felt careless; my partner was another professional snow worker on a day off.

“Cool. 4-20. Have a great day,” he concluded as he strode past us and down the ridge.

It took a few more quiet minutes to finish our transition. And for me to digest the encounter.

“That was pro,” I said.

“Very,” my partner replied.

Young Gun had just modeled community-building backcountry communication. And to two backcountry elders.

What impressed me was Young Gun’s purposeful communication. Specifically, on a morning when a natural impulse is to be tight-lipped or even territorial, he opened a conversation. He found out where we’d be, relayed his group’s plans, and made sure people knew how to raise help if trouble arose. He could be fairly confident his party wouldn’t be above us and put us in danger, that we wouldn’t do the same to them, and that if either situation did happen, the two parties could communicate clearly, without yelling and arm-waving. And Young Gun did it without slowing anyone’s morning commute. Pro, indeed.

Good thing my partner had the sense to bring his radio.

Avalanche classes emphasize the need for clear communication within groups. As the number of riders in the backcountry swells, positive communication between groups grows ever more important. Sure, it’s easy to bemoan those ballooning numbers, to be nostalgic for the days when the backcountry felt like an all-to-yourself discovery. But the conflux of marketing, social media, and a pandemic mean that things have changed.

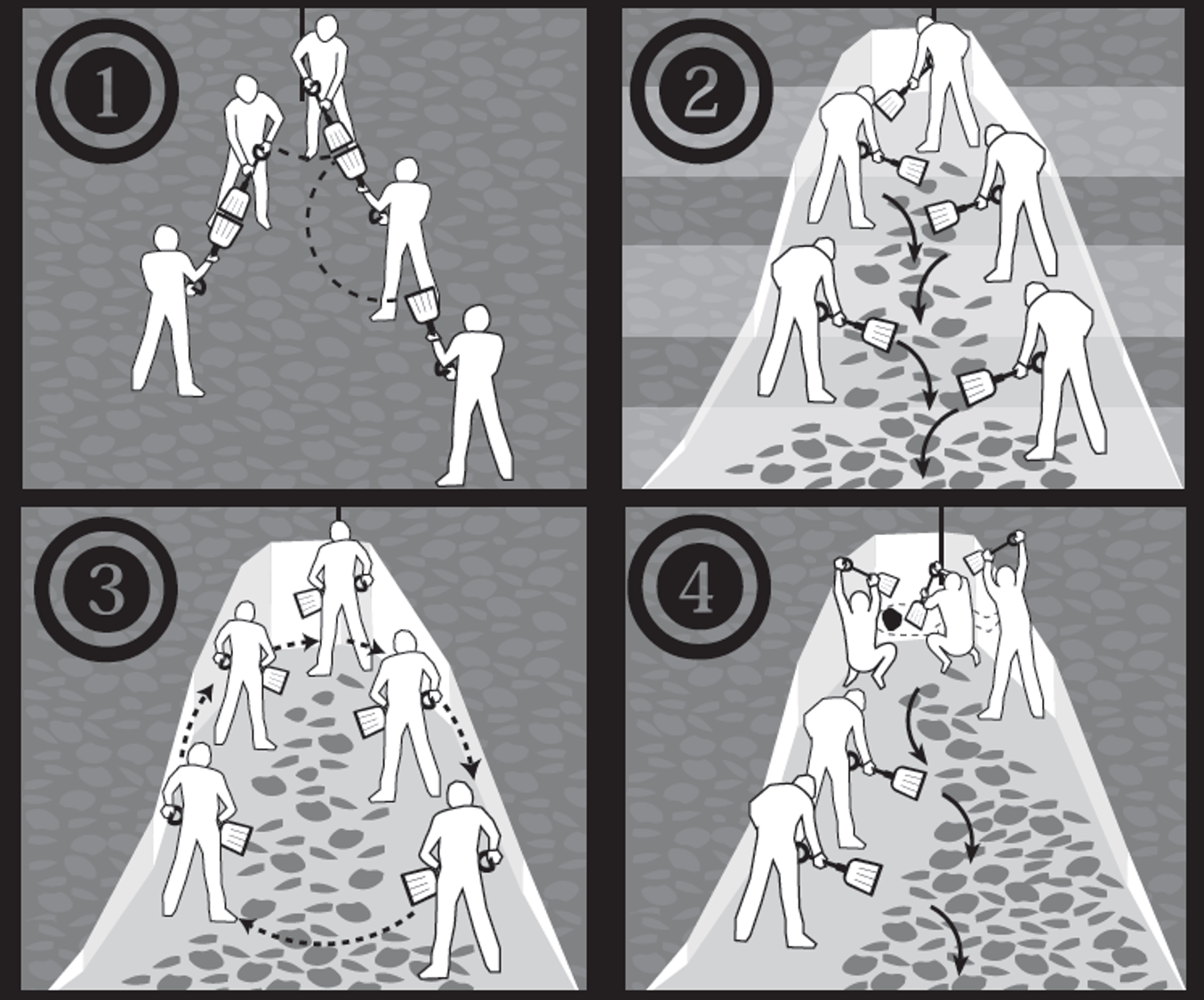

Those changes are probably lasting. And they raise previously remote dangers to the fore. In fact, adding a just a few more people may increase the chances of inter-party accidents dramatically (geeky proof but with images, p. 18-20). Avoiding overhead hazard may mean avoiding other parties’ triggered slides, not just natural avalanches. Assessing a run may mean assessing it for consequences not only to me and my party, but to people below as well. It may mean using community radio channels in areas where you're used to doing your own thing or never used to see people.

Perversely, the opportunities for communicating seem to coincide with the moments we’re least open to talk. Arriving at a trailhead and finding another three carloads of people putting on skins. Another party catching up as you’re breaking trail.

A few things might help start those conversations and make them easier with practice.

* Offer something up. Start with your group’s plans. A thank you for the uptrack. Your group’s radio channel or turn-around time.

* Focus questions and conversation on factors that affect both groups’ safety.

* Keep it brief.

* Stick to any agreements unless you can communicate directly. For a reason why, see this accident report and the lawsuit that followed.

We never saw Young Gun after our conversation that morning. We had our destination to ourselves, untracked. We wouldn’t have made last chair back to the summit if we hadn’t caught an uptrack – probably his – part way back to Skook. There’s old-man strong, but there’s no old-man fast. And there’s Young Guns showing old dogs new tricks.

image courtesy Carl Zoch

Post #18 - 1/19/21

New Forecast Platform!

By blase reardon, FAC Director

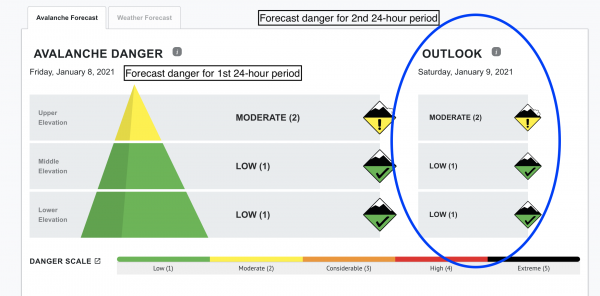

Yep, the forecast looks different this morning. New icons, new color scheme. And two days. What gives?

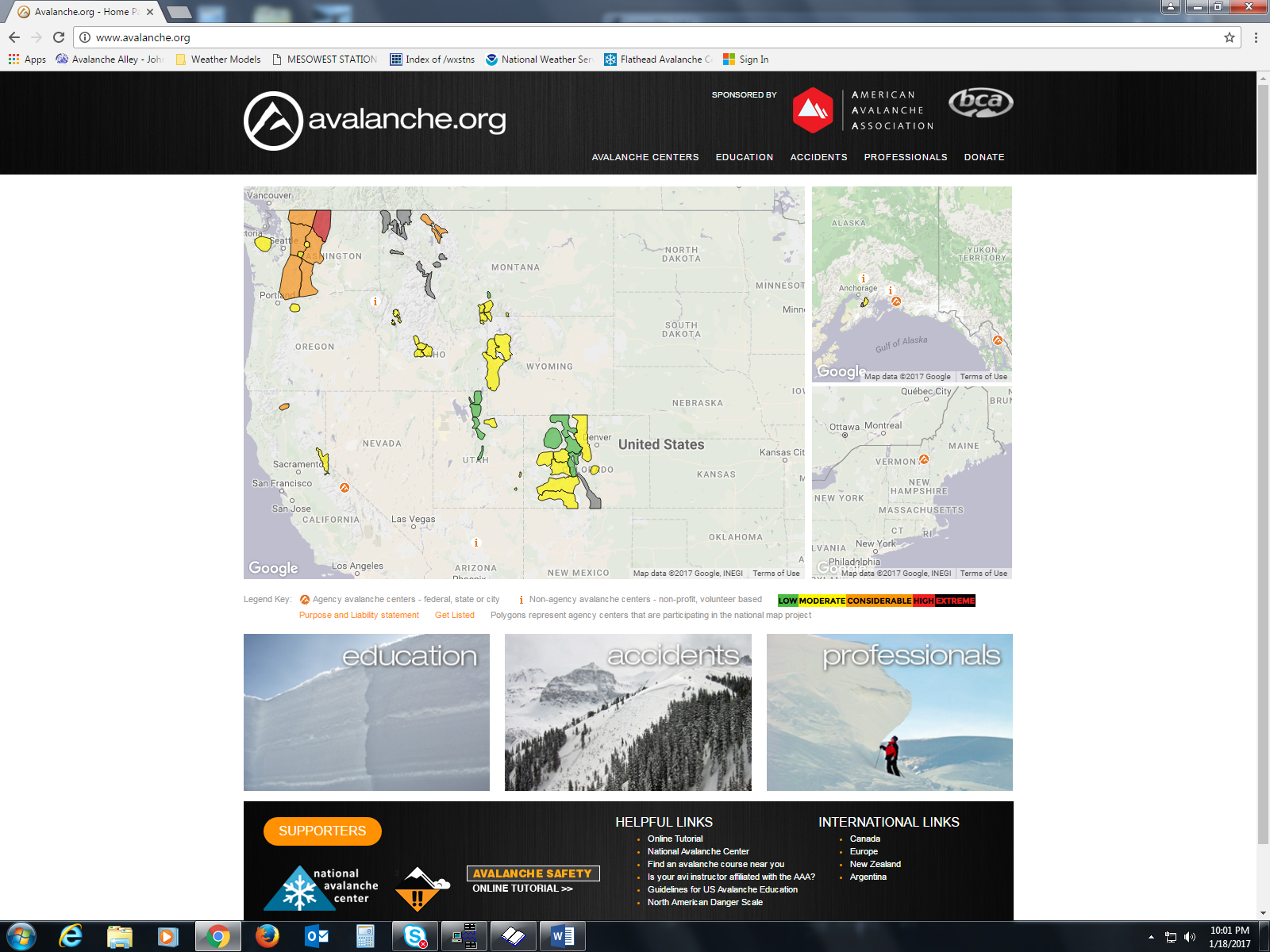

We’ve adopted a forecasting platform developed by the USFS National Avalanche Center and shared by a number of regional avalanche centers across the country. The forecasting platform is the back end of what you see on the website; it’s where we assign the danger ratings and problems and input the text for the different sections of each day’s products. The switch from one behind the scenes on our own website to a shared platform has several advantages:

- A common look amongst avalanche centers, so forecasts will look familiar when you travel.

- Longer forecast period

- 24-hour weather summaries for each zone

- Ability to leverage multiple centers’ resources for future web development costs

Let’s detail each of those in turn:

Seeing a familiar format when you travel to other areas makes it easier to use information in the daily forecasts. You don’t have to wonder if a different icon for Storm or Persistent Slab avalanches means something different. You know where to look for the weather forecast. Same for people visiting here.

A longer forecast period helps people better plan their backcountry travel. Our daily forecasts will now expire after 24 hours, instead of 17. And we’ve added an outlook for the next 24 hours. There’s more uncertainty with that outlook than the daily forecast, because it’s less real-time. No weather data that’sonly a few hours old when we publish, no obs from the day before, and a weather forecast that’s slightly further into the future. Nonetheless, it should give you a clear idea of how and where we expect the avalanche danger to change. If, on a Tuesday, we call it High for Wednesday, and then a storm weakens as it approaches, we might wind up calling the danger Considerable on Wednesday morning. We’ll still make the most accurate calls we can. And you’ll know we expect, and can plan accordingly.

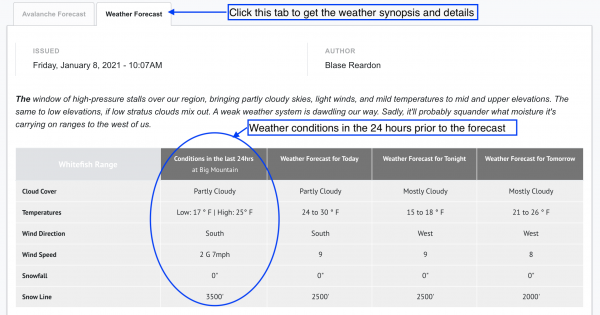

The weather forecast for each zone includes a summary of conditions for the past 24 hours at a representative station. It’s the left hand column of numbers. That should make it easier to see how conditions will change over the next 36 hours. That's visible at the bottom of each zone's forecast. To see the weather synopsis and the forecast for all 3 zones. click on the "Weather Forecast" tab just below the bottom line.

We’ll share the costs of future changes to the forecasting platform with other regional avalanche centers. We can leverage local contributions instead of absorbing all costs. If avalanche problem icons change, we share the cost of developing new graphics with all the other centers that use the platform. While that’s an example of a small change, others might be too costly for the Friends of the Flathead Avalanche Center to shoulder on their own.

To make this happen, we made some tradeoffs. For example, you won’t receive the entire forecast by email any longer. That may change next season. Instead, you get the danger rating, outlook, and bottom line for all three zones. Go to the website for the full forecast for each zone. While the image galleries that accompanied each problem description have gone away, we can now incorporate images into the text with conditions-specific captions.

Give the new format a try for a few days and let us know what you think ([email protected]). Thanks to the Friends of the Flathead Avalanche Center and the National Avalanche Center for making this happen!

Post #17 - 1/12/21

Season Update

By, Mark Dundas, FAC forecaster

I stare out my dining room window at a yard of brown grass and a pathetic looking snowpack on the lower slopes of Columbia Mountain. Judging from this picture, one would assume the Flathead Basin snowpack is in dismal shape. Fortunately, that is not the case.

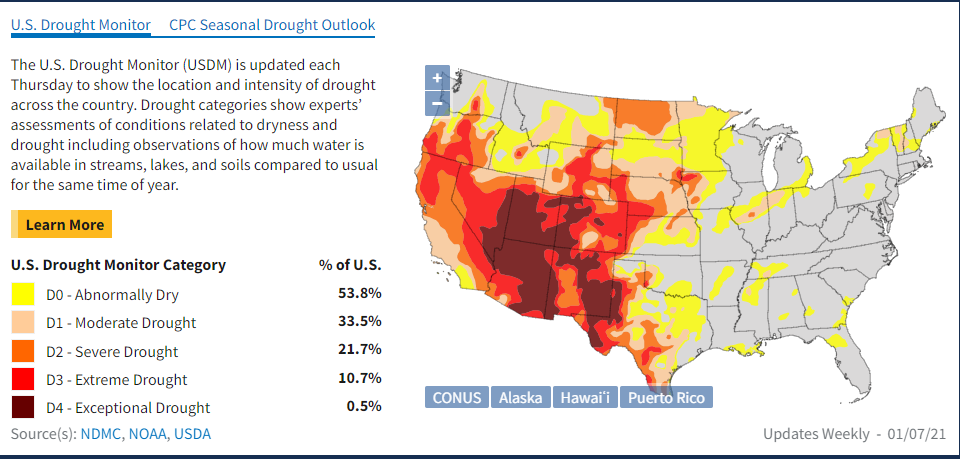

Most of the mountain west is suffering from an extended drought, with large swaths classified at extreme or exceptional drought, with a well below-average snowpack. Fortunately, the Pacific Northwest (Washington, the panhandle of Idaho, and Northwest Montana) has received enough moisture to escape drought status with a mountain snowpack near or above average. Locally, the Flathead Basin contains 97% median SWE (Snow Water Equivalent) and 107% median precipitation as of January 12. Surprisingly, our two low-elevation snotel sites report 93-100% median SWE. A useful link to monitor NRCS SNOTEL sites: Columbia River Basin

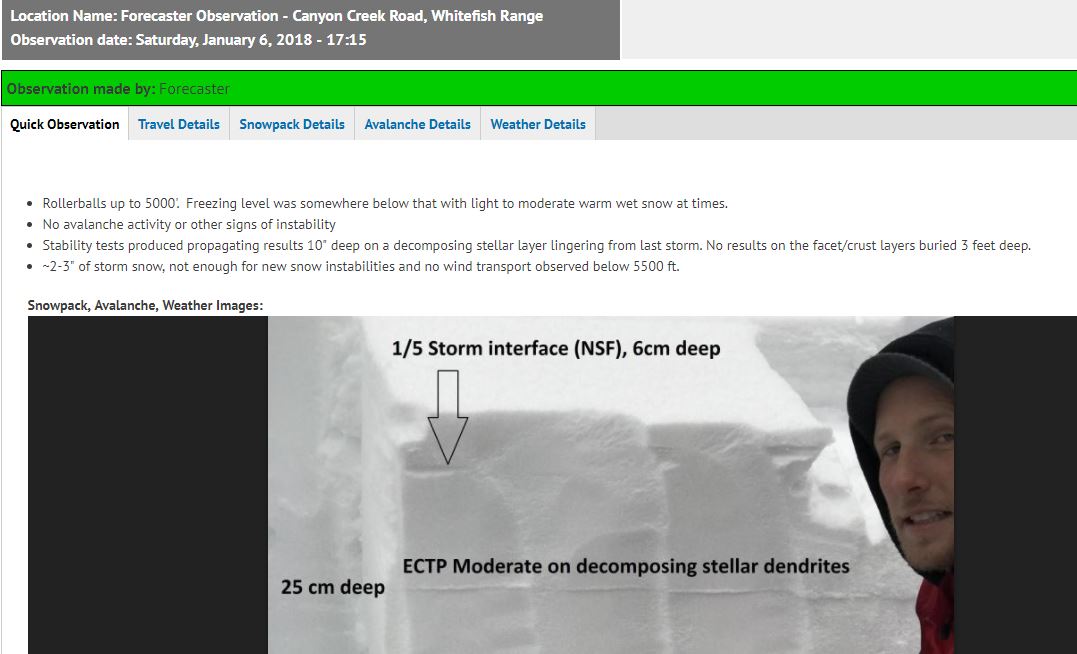

Following a prolonged period of high-pressure, FAC began issuing daily avalanche forecasts on December 9. The danger rose on the 10th as a warm storm dropped over 1” of water at Stahl Peak and Flattop. Rain and wet snow formed a surface referred to as Mean Mr. Custard for the poor skiing quality left in its wake. Seasonably cool temperatures resulted in a stout crust capped with a thin layer of faceted snow. Several days of snowfall formed a slab on top of the crust, which proved to be problematic outside the boundary of WMR. Following several skier triggered slides on this layer in the Canyon Creek area, we listed Persistent Slab as an avalanche problem on December 19.

Starting December 20, back-to-back Atmospheric Rivers soaked parts of our area, with each storm depositing over 1” of water. The second event included freezing levels up to 6000’ during Winter Solstice. We issued an Avalanche Watch during the height of the storm as large destructive Persistent Slab avalanches failed on buried weak layers. Bluebird conditions around Christmas allowed for great views of the wreckage that spanned all three elevation bands. Soon after, the December 22 (Solstice) crust became a ranking member of the Loyal Order Of The Persistent Weak Layer club.

A glide crack noted Christmas morning failed by the following day. Imagine that, a glide avalanche in December!

Moisture returned in earnest as another warm, wet storm deposited over an inch of water in the Swan Range and the Whitefish Range on the 26th and 27th. Natural and skier-triggered surface slides occurred, but we do not have documentation that any of these slides triggered a larger avalanche on a buried weak layer.

Holiday storm #4 arrived just before the New Year with 1.7” of water in the Swan Range, where the hazard rose to HIGH.

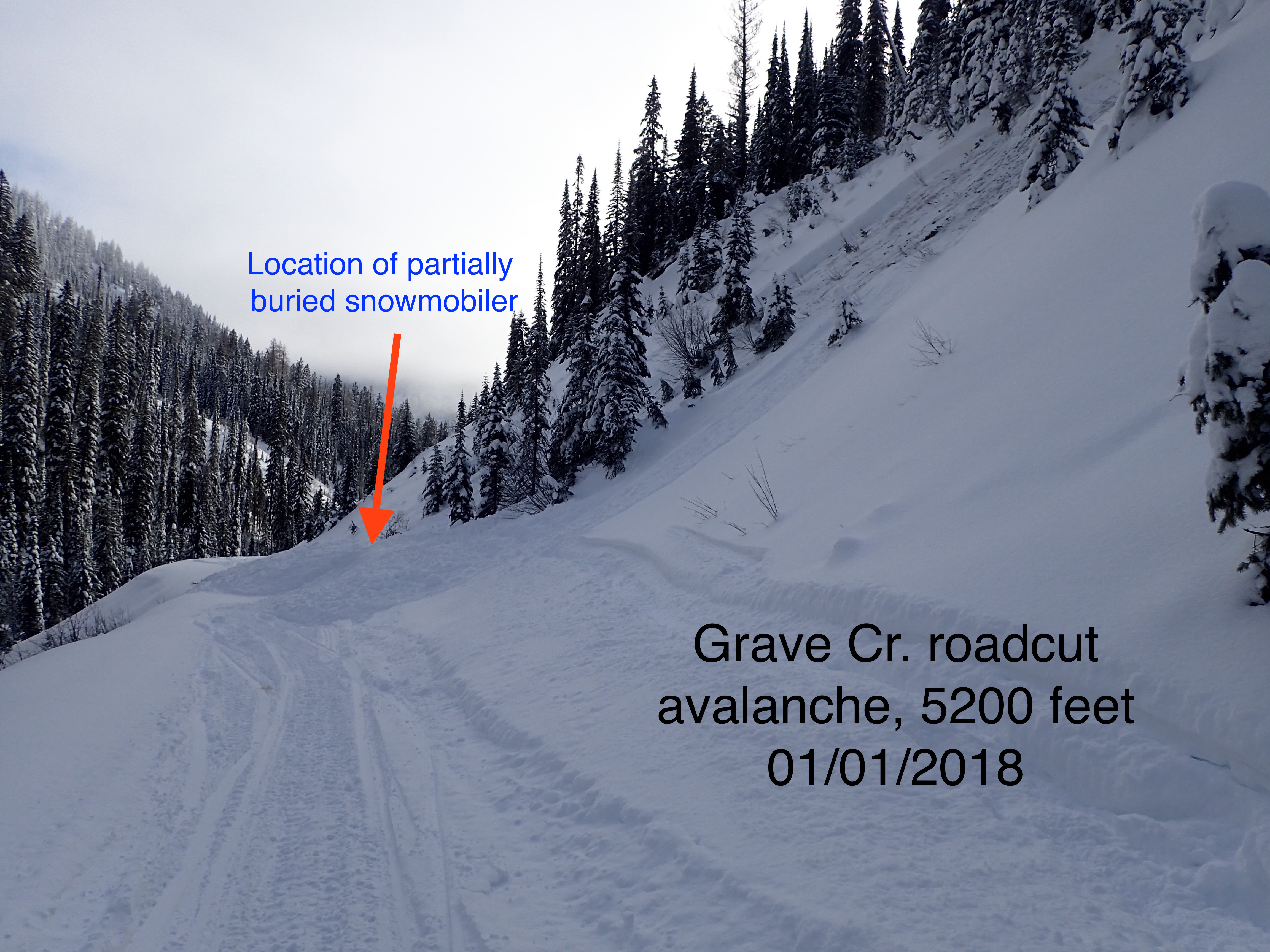

New Years Day kicked off with three skier-triggered slab avalanches. Slides broke about a foot deep on steep, northerly slopes around 6300 feet. Two of these were D2 in size - enough debris to bury or injure a person. 2 Slides released on convex rollovers, 2 failed at the 12/22 interface, and all three occurred well below ridgelines. The northern Whitefish Range, the southern Whitefish Range, and the Flathead Range were locations for these slides. The Flathead Range party described looking down and saw "a nice gladed slope with plenty of trees." In all three cases, the near-surface snow had consolidated markedly from the previous day, either from cross-loading or warming.

One last Atmospheric River entered our area on New Years’ weekend, soaking interior Glacier Park with 2” of water, about half that amount in the Whitefish Range. At the same time, the Swan was left relatively high and dry. Moderate to strong winds accompanied this storm and lasted through the workweek. Observers reported a handful of wind slabs with at least one stepping down to a buried weak layer triggering a Persistent Slab avalanche. The January 2 faceted crust joined December 9 and 22 to form our elite persistent weak layer club.

Unusual conditions create unusual avalanches. Observers noted several glide cracks in the Flathead Range, with one in southern Glacier Park. Glide cracks and failure are not new to our area, but December and January are a bit early to be worrying about those beasts. Adding to our list of concerns were reports of reactive buried surface hoar mainly in the Flathead Range. Yet another persistent weak layer to monitor. What else could go wrong?

Seriously? Another Atmospheric River entered our area on January 12. The forecast is for copious moisture, warm temperatures, and windy conditions. We issued an AVALANCHE WATCH stating: Heavy, wet snow, blowing snow, and rain on snow may overload the snow surface and buried weak layers resulting in widespread areas of unstable snow and natural avalanches. If you get out in the field, please let us know what you see.

Post #16 – 3/25/2020

Avalanche Airbags and Terrain

By blase reardon, FAC Lead Forecaster

Earlier this winter, a website user sent us an observation, then followed with a key question. My answer, slightly edited and expanded, is below. It’s a good summary of airbag effectiveness as we currently understand it.

“I've seen that in the past week, 2 snowmobilers (Lake Dinah, MT and Farmington, Utah) died in avalanches WITH airbags, deployed…. Do you have any information as to why snowmobile riders' airbags are failing to save them?”

Good questions. The short answer is probably terrain. Avalanche airbags aren’t as effective in situations where the victim is caught from above and doesn't travel far or on avalanche slopes without a good runout.

Airbags work on the principle of inverse segregation, which is a term for what we observe when we shake a can of mixed nuts. Larger nuts, like Brazil nuts, rise to the surface while smaller peanuts wind up on the bottom of the can. The effect is due to the difference in surface area. Inflated airbags give a rider an increased surface area, so with an inflated airbag, a rider essentially changes from a peanut to a Brazil nut and rises to the top of the debris.

For a rider to rise to the surface, however, the can has to be large and shaken for a long time. Debris that doesn't fan out doesn't allow the process to work; it's like shaking nuts in a tall glass. It takes more shaking for the big nuts to rise to the top than it would for the same amount of nuts in a wide-bottomed can. So a short ride in avalanche debris or a situation where the debris gets funneled doesn't allow the rider to rise to the surface.

A large nut. This rider inflated his airbag after he triggered a wet slab. His partner found him at the bottom of the slope in this position. March 17, 2015. Ashcroft, CO.

In the Lake Dinah accident, the rider with the airbag was roughly in the middle of the slope when the avalanche released from above. He wasn't carried far, so he couldn't rise above the debris that covered him. He may also have been caught in the trees, which prevented him from moving downhill. In other words, the can didn't shake long enough.

In the Farmington Lakes accident, the rider may have also been caught from above, though he was much closer to the crown when the avalanche released. More importantly, the slide path had no run out; the debris stopped abruptly on a frozen lake, resulting in a deep burial. A feature like this is termed a terrain trap. The rider may not yet have risen to the surface, or he may have been overrun from behind when he stopped before debris behind him did. Or in the terms of our mixed nuts metaphor, the can stopped shaking.

I'm not sure airbags are less effective for snowmobilers. These are two instances that happened to be close in time, so it might be more random than pattern. If there is a difference in airbag effectiveness between skiers and snowmobilers, it might be due to the differences in where and how riders approach a slope and tend to get caught. Skiers tend to enter top down, which can put them closer to the crown and more in the top/ back of the debris. Snowmobilers tend to ride up slopes from the bottom, so they may be more prone to being overrun by debris and have less time for the airbags to work.

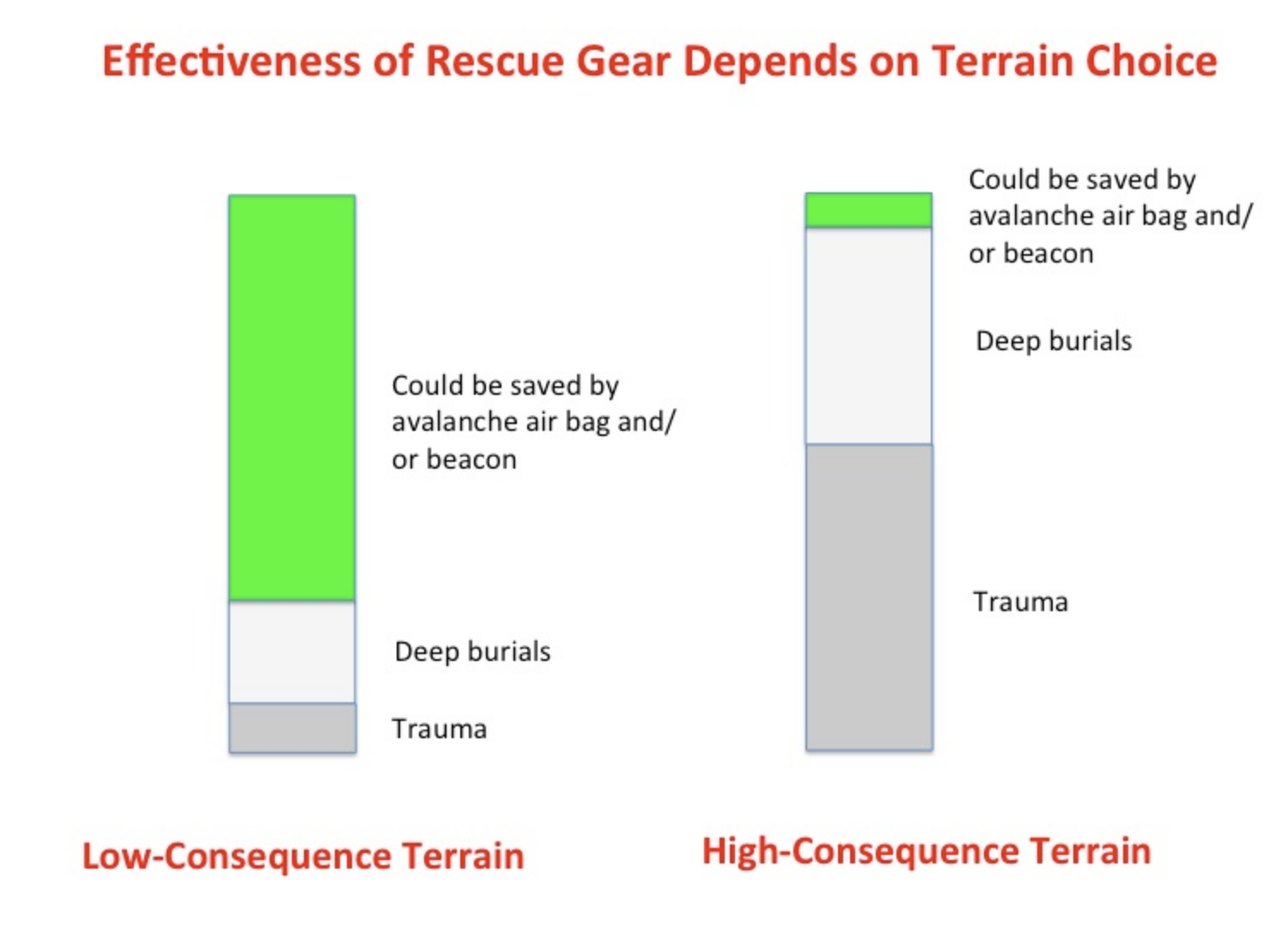

The bottom line is that even when using airbags, terrain selection remains critical.

Short slopes above terrain traps don’t provide enough time or space for an airbag to work. So regardless of whether you are riding a machine or a plank or two, you want to recognize and avoid terrain traps – those where the debris can pile up deeply, like gullies, roadcuts, and yes, frozen lakes. This video from the Utah Avalanche Center shows how that can happen and its potential consequences.

So how effective are airbags? Let’s take a closer look.

Airbags, like seat belts and airbags in your car, aren’t a panacea. The best study to date of their effectiveness shows airbags can, however, significantly reduce the likelihood of critical burials (head under the snow with impaired breathing) if you’re caught in a slide large enough to bury you. Because of that, they can significantly improve a person’s chance of surviving such slides if caught.

The study referenced above calculates that if you’re caught in a large slide (D2 or larger) without an inflated airbag, you have roughly a 54% chance of a critical burial. In other words, five out of ten slides turn critical. An inflated airbag, however, may reduce the likelihood of a critical burial to 19%, or about two in every ten times a person is caught. That’s a significant improvement: three out of your ten buddies who get caught in D2s avoid a critical burial just by inflating their airbag.

So you’re less likely to get critically buried. Are you more likely to survive? Without an inflated airbag, it appears about 22% of people caught in large slides die, most of them in critical burials. That’s about two in ten, and some of those victims die from trauma. With an inflated airbag, the mortality rate looks to be 11%. That’s still bad – one in ten people, including those with inflated airbags. But it’s a 50% improvement over not having an inflated airbag. Most of us would jump at a prophylactic that reduces our chance of dying from COVID-19 by 50% right now.

Note the phrase “inflated airbag” in the paragraphs above, as opposed to “wearing an airbag.” That’s because in the study I referenced, about 20% of victims wearing an airbag pack did not or could not inflate the bag when caught. The reasons for this included failure to deploy the bag, maintenance errors, device failure, and destruction of the airbag in the slide. Familiarity with airbag use can minimize the first two issues; terrain selection free of rocks and trees may minimize the latter.

Another reason that airbags aren’t a cure-all is that they don’t protect against trauma incurred while carried in an avalanche. Bruce Tremper, former Director of the Utah Avalanche Center, has a great discussion of that issue here. And he has a great summary of how terrain choice can influence the effectiveness of airbags:

As usual, our choice of terrain is far more important than rescue gear. Un-survivable terrain will always be un-survivable. In terrain with few obstacles, terrain traps, sharp transitions and smaller paths, avalanche airbags have the potential to save significantly more than half of those who would have otherwise died. And that sounds pretty good to me.

It sounds good to me too, so I wear an airbag pack nearly every day in the backcountry. And I keep a sharp eye out for terrain traps.

Bruce Tremper’s graphic depicting how terrain choices can reduce the effectiveness of airbags.

Thanks to Michael Javorka for the question that prompted this blog.

Further reading:

The effectiveness of avalanche airbags. Haegeli, Pascal et al. Resuscitation, Volume 85, Issue 9, 1197 – 1203

Avalanche Airbag Effectiveness - Something Closer to the Truth. Tremper, Bruce. Utah Avalanche Center.

January 18, 2020 Farmington Lakes, UT Accident Report

January 1, 2020 Lake Dinah, MT Accident Report

Post #15 – 1/9/2020

Likelihood is not Danger

By blase reardon, FAC Lead Forecaster

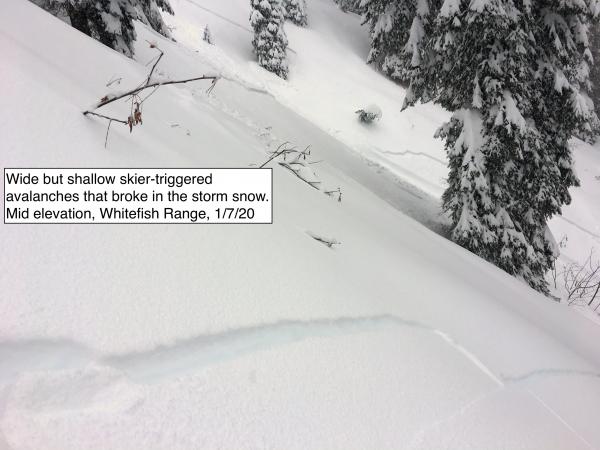

Sometimes it’s silly easy to trigger avalanches, like it was Tuesday (Jan. 7) in Canyon Creek, in the southern Whitefish Range adjacent to Whitefish Mountain Resort. As we skied down to the canyon floor, we triggered a half dozen avalanches. The crowns on these slides were up to 100 feet wide, and we triggered a few remotely. We saw some similar slides that released naturally. Another party reported similar conditions.

Scary, huh? Actually, no. The avalanches broke 3 to 6 inches deep, so the debris was shallow and soft. Getting buried or injured on one of these slides was unlikely. Getting knocked off your feet and pushed headfirst into a treewell would have been bad. But that was a hazard my partner and I could mitigate by riding one at a time, not skiing above each other, and keeping each other in sight at all times. With those practices, we could help each other out of trouble. So while the likelihood of triggering avalanches was high, the danger was not. The snow was moving, but we were unlikely to get hurt.

The flip side of that day is one where I don’t see any avalanches and few if any signs of instability. Yet I scrupulously stick to low angle slopes and avoid avalanche runouts, maybe even avoid some terrain or drainages altogether, despite great riding conditions. What’s up that? If I’m not likely to trigger a slide, why ski like a nervous bunny?

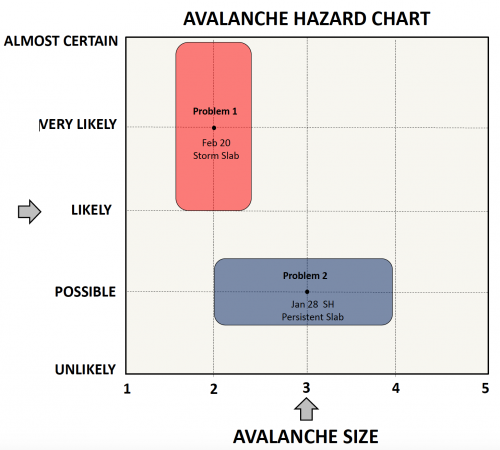

Avalanche danger is a combination of likelihood and consequences. From my tour Tuesday, the likelihood of triggering avalanches was high but the consequences were low. It was like wading through a pack of unfriendly Chihuahuas. Keep your hands high and you won’t lose any fingers. In the second situation, the likelihood may be lower but the consequences would be severe. Like sneaking into a backyard when you’re not sure if the big guard dog – a Rottweiler, maybe – is asleep. Not much you can do to keep yourself from getting chewed if you wake it.

The graphic below shows one way to visualize this distinction for a random day. The horizontal axis is avalanche size – a proxy for consequences. The vertical axis is likelihood. The red box is the Chihuahuas; the blue box is the Rottweiler. I’ll take Chihuahuas any day.

From Statham, G., Haegeli, P., Greene, E. et al. Nat Hazards (2018) 90: 663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-3070-5.

We assess both likelihood and consequences for any given day’s danger rating. We haven’t blown the danger rating if you see lots of small slides and the hazard is Considerable, like it was Tuesday. Nor are we crying wolf if we call it Considerable and you don’t see any slides. We’re giving you our best guess at the kind of hazard that exists on a given day – both likelihood and potential consequences - so you can choose terrain where the riding is fun and your risk of getting chewed up is lower.

Your observations help us to create accurate forecasts, help to verify our danger ratings, and supply information that will support the following day’s forecast. So please, let us know what you see when you’re riding. And if you think we got it wrong, let us know that too, so our products are as accurate and helpful as they can be.

Post #14 - 1/2/20

The alligators are back, but they might be more vicious this year.

By Zach Guy, FAC Director

You might remember our analogy last January when we had a buried surface hoar problem at mid-elevations. We described the situation in terms of a moat surrounding a castle. If you could cross through the mid-elevation moat without getting chomped by alligators (the surface hoar), then you could enjoy the castle...upper elevation grandeur free of surface hoar. Well the alligators are back this year, but under different circumstances. Their moat is larger and poorly understood right now, and there may not be a castle at all.

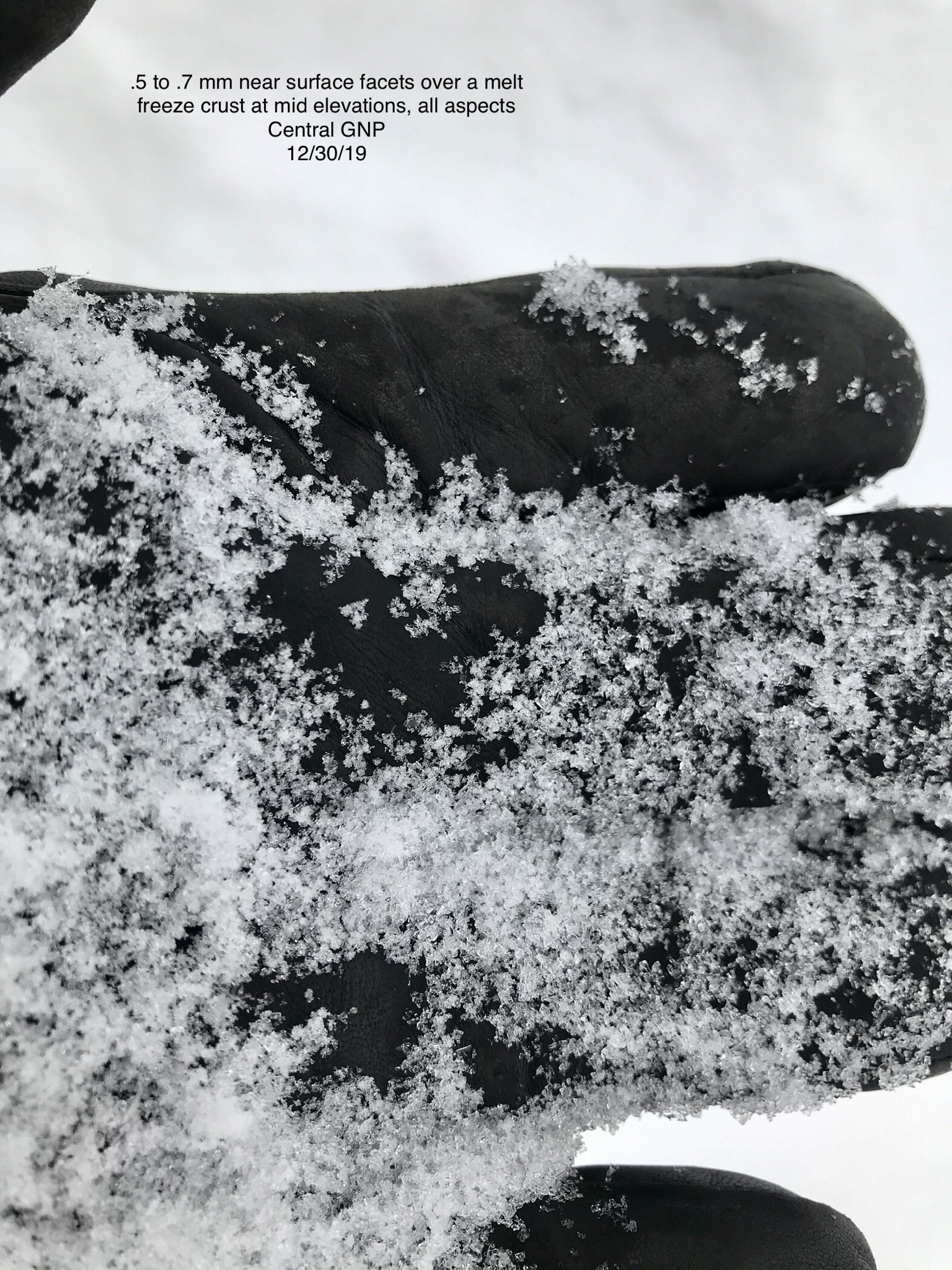

The story starts with our solstice storm, with its high freezing levels followed by a warm sunny day. This left a melt-freeze crust up to about 6,100' on all aspects, and to higher elevations on southerly aspects. We are calling this the Christmas Eve Crust. Then, we had two separate surface hoar events during the holiday week. The first event occurred on Christmas Day as clear skies sagged south from Canada. From that event, we observed widespread surface hoar growth in the Northern Whitefish Range starting at 5,700' and going all the way to ridgetops. In the subsequent days, dribs and drabs of low-density snow under light winds likely buried this layer. The second event occurred on December 30th, but this one was more widespread. And unlike last year's surface hoar event, the cloud deck that provided the fuel for this surface hoar growth rose higher, reaching well into the alpine. The photo below shows the cloud deck rising to 8,000' in Glacier National Park on December 30th.

We had limited time to gather information about the distribution of the December 30th surface hoar event before it was buried. It was observed from 5,000' and higher near John F Stevens Canyon. Near Paola Ridge in the Flathead Range, observers reported it started at 5,700'. In the Skyland area, 6,400' and above. On Mt. Brown in the Park, 6,000' and above. In the Southern Whitefish Range, 6,500' and above. Near Holland Lake in the Swan, 6,000' and above, and mostly on north facing aspects. To complicate the matters, there is also a near-surface facet layer joining the moat party. Near-surface facets are smaller weak grains that often form under similar weather conditions as surface hoar, but within low-density snow on the snow surface. The near-surface facets appeared to form in areas that had seen only a dusting of new snow and colder temperatures during Christmas week, namely the Northern Whitefish Range, the Flathead, and Glacier National Park. This layer isn't dependant on a moisture feed from stratus clouds, rather, it feeds off of the warmth provided by melt-freeze crusts and strong temperature gradients with cold air. So we have found near-surface facets at the same elevations and aspects that the Christmas Eve crust was observed: up to 6,100' on all aspects and higher on southerlies.

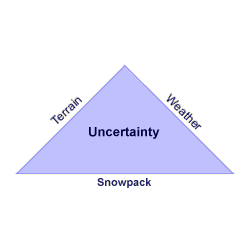

Now here's where the plot thickens. We had a freezing rain event the night of December 30th at all elevations, which formed a thin glaze of ice directly on top of these weak layers. We speculate that the freezing rain destroyed the surface hoar and near-surface facets in some places, but capped them in others. In areas where this freezing rain crust is thinner, you are more likely to find weak layers preserved beneath it. We have noted the crust is thinnest (or non-existent) the further east you go towards the Continental Divide. So now we have a nightmare of a crust sandwich. A stout melt-freeze crust (the Christmas Eve Crust), with near-surface facets and/or surface hoar in the middle, capped by a thin, breakable rain crust (the New Year's Eve Crust). In some places, it may be just an open-faced sandwich, lacking one of the two crusts. Either way, it is scary. In the last few days I've heard terms like "creepy" or "bag of #%@#" used by snow professionals in the region. And because of all of the dynamic processes going into the making of this Holiday Sandwich, and because it was so quickly buried, we have a poor handle and a lot of uncertainty on how widely it is distributed across our terrain. If there's one message to take home from all of this, it is that the most recent weak layer smorgasbord is complicated and variable, and it might lead to surprises. Our forecasters are hustling around the field to try and wrap our heads around this one.

During our first loading event on the Holiday Sandwich, we issued a Special Avalanche Bulletin. This was to help highlight the unusual and dangerous conditions that were developing with the foot of dense snow that arrived. The storm, as forecasted, didn't appear to be enough to create a large and widespread natural avalanche cycle (and thus, an Avalanche Warning), but it was enough to let the alligators out of their den. We ended up getting more snow than forecasted, and likely saw a fair amount of natural activity. On Mt. Brown in Glacier Park, Clancy reported touchy, remotely triggered storm slabs that propagated surprisingly wide distances, failing on the surface hoar. Even though the slab over these layers is quite soft and relatively small right now, the thin rain crust capping the surface hoar helps communicate failures further distances. Very hard over very soft is a bad combination. In JFS Canyon, Ted and Adam remotely triggered a similar slide that failed on near-surface facets. And tragically, south of our forecast area near Seeley Lake, 2 snowmobilers were killed in an avalanche that reportedly failed on the same layers. That area picked up roughly twice the amount of snow that we saw in our forecast area, but it is foreshadowing for what's to come.

Right now, the Holiday Sandwich is buried about a foot deep under a soft slab, except for wind loaded areas, where slabs will be thicker. Feedback should be fairly reliable and consequences aren't huge unless you're in the wrong type of terrain. We're still calling it a storm slab, although it is already showing some remote triggering and widely propagating potential that is characteristic of persistent slabs. Looking ahead, we have more storms on the menu. The slabs will thicken and develop into our new persistent slab problem. We have another decent storm on Saturday. Will that be a knockout punch or keep us on the teeter-totter? Regardless, keep your cards close at hand and hold on tight in the coming weeks. Things could get scary. Conservative terrain choices are the best way to handle a scary snowpack.

Post #13 - 3/13/19

How much did it snow? Estimating snow accumulation from your breakfast table.

By Zach Guy, FAC Director

At the FAC, we forecast for the regional avalanche danger, but there are often variations to this danger at the basin scale. One of the big players for this variation is snow totals. The avalanche danger is often higher in areas that saw more snow. And yes, the powder is deeper too. Thus, from both avalanche safety and recreation perspectives, it is valuable to be able to read snow totals and to understand the nuances and potential errors associated with these instruments.

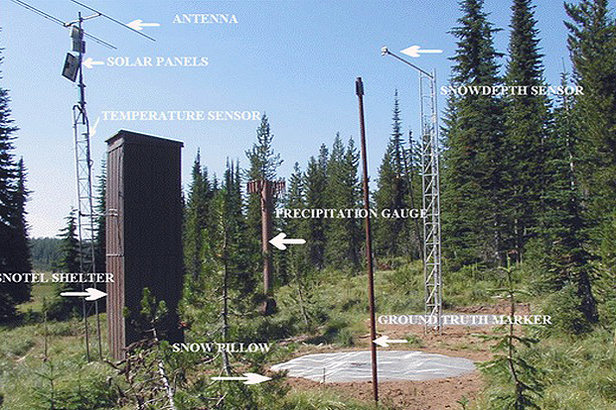

We have a handful of SNOTEL sites and a number of other precipitation or snow depth sensors that we rely on for estimating snowfall during a storm. If you are looking at a standard SNOTEL site, there are 4 data outputs to consider: snow water equivalent (SWE), precipitation accumulation, snow depth, and air temperature.

Photo of a typical SNOTEL site. Image courtesy USDA NCRS

Snow Water Equivalent

SWE and precipitation report on the same characteristic, but they are measured quite differently. SWE is measured from a snow pillow: imagine a scale – like one on which you weigh yourself at the gym or doctor’s office - placed underneath the snow. It measures the total weight of the snowpack, and just like the doctor, we can monitor how obese the snow is getting after a storm. This is my #1 most valuable tool for forecasting. Snow pillows record the change in mass during a storm, a value which doesn’t vary with air temperature, so they are the best measure of load produced by a storm. They report in inches of water equivalent – how much water would be in a glass if the snow were melted.

The precipitation gauge also measures the water content falling from the sky, but instead of weighing the snowpack as it accumulates on the ground, it weighs the snow that falls into a bucket. Precipitation buckets have an anti-freeze solution in them so that snowfall melts upon arrival, and the gauge calculates how much water has been added with each storm. SWE and precipitation should align closely; if they don’t, there’s reason to be suspicious of the data. During exceptionally windy storms, the precipitation buckets can be less reliable because the snow isn’t falling straight down into the bucket. Occasionally the precipitation buckets get clogged by a cap of snow during big storms. However, the precipitation buckets can be useful in the early season for identifying rain events that could translate to snow at higher elevations, before the SWE snow pillow has developed. Furthermore, during spring melt, the SWE snow pillow can be losing weight as the snowpack drains concurrently with snow water accumulating at the surface - thus the precip bucket can be more effective for capturing accumulation.

Snow Depth

Finally, there is snow depth. In your yard, you can measure snow depth with a ruler, the same way a doctor measures your height with a yardstick. Automated weather stations rely on ultrasonic waves, the same way bats stay oriented when flying in the dark. The ultrasonic sensor is placed well above the snow surface and shoots an ultrasonic ping down at the snowpack. The time it takes for the signal to bounce back to the instrument is used to calculate the height of the snowpack above the ground. The change in height of the snowpack gives a measure of snowfall. For instance, if the snow height is 90 inches before the storm, and 96 inches after, at least six inches of snow accumulated during the storm.

The snow depth – or height - reading is the most prone to data error or misinterpretation for a number of reasons. First, during heavy snowfall events, the ultrasonic wave might reflect off of snowflakes falling through the air, rather than the snow surface. You might see some unexpectedly big readouts which require common sense filters. Did the snow depth really increase 14 inches in one hour? Probably not. The other common source for misinterpretation is due to the snowpack settling (or shrinking in height) concurrently with the arrival of new snow. This effect is more pronounced during prolonged storms when the snowpack consists of feet upon feet of relatively low-density snow. In other words, the total snow depth might be five feet of fluffy snow, but with the arrival of another foot of snow, that existing five feet compresses to four feet deep as the new snow piles on top. So the snow depth doesn't change, even though it actually snowed a foot. If the existing snowpack is dense and has had plenty of time to settle, such as during the spring or after a long dry spell, the change in snow depth is a fairly reliable measure of new snow.

During ongoing big snowfall events, I don’t trust the snow depth as a tool for calculating overnight snow totals. Instead, I look back to SWE and incorporate the 4th instrument, air temperature. During a “normal” snowfall event here in NW Montana (is there such a thing?), snow falls somewhere in the neighborhood of 12:1 snow to water ratio, producing snow that ranges from 6% to 10% density. These ratios vary wildly with atmospheric conditions, air temperature, and the amount of wind damage that smashes snowflakes together as they fall. If you see air temperatures are in the mid 20’s during the storm, a general rule of thumb is to multiply SWE by 12 to get the amount of new snow. In other words, one inch of SWE means 12 inches of snow fell. If the snow accumulates with air temperatures in the 30’s, you are looking at ratios from 10:1 or 5:1. If the air temperature is 20 F or lower, ratios can be 15:1 or could reach beyond 30:1. This link has a conversion chart from NOAA, if you really want to geek out.

The depth of new snow for a given amount of water depends on the air temperature. Image courtesy of AccuWeather

Wind

Another source of error for all of these instruments is wind. SNOTEL sites are usually placed in areas that are well protected from winds, so they tend to be the most reliable during typical winds. We have snow sensors and precipitation buckets located in more wind-affected areas though, such as Big Mountain summit or above John F Stevens Canyon. It is important to consider wind drifting when looking at these sensors. Wind can either scour away new snow or drift it into misleading high totals. Some stations have wind sensors at or near the snow depth plot, but sometimes you have to infer the wind effects by looking at nearby wind sensors. The stronger the wind event, the less I trust the snow and SWE measurements.

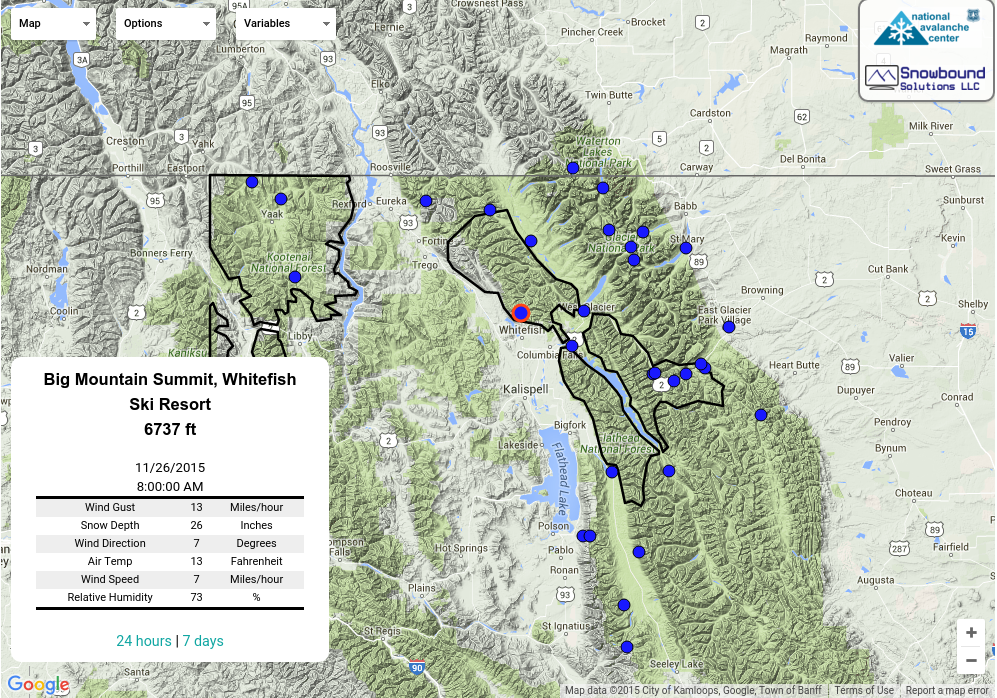

Weather Station Resources

For a map of most of our local sensors, this is a great resource. Our favorite mountain SNOTELS are Stahl Peak in the Northern Whitefish Range, Flattop in Central GNP, and Noisy Basin in the Swan Range. Lower elevation SNOTELS such as Graves Creek, Emery Creek, and Pike Creek are also helpful. Other useful mountain stations include our Big Mountain Station (owned by FOFAC and maintained through a partnership with WMR ski patrol), several weather stations above and on the floor of John F. Stevens Canyons, and several sensors in Glacier Park operated by the USGS. A few of these stations are unlisted on our map but can be found here. FAC and FOFAC recently finalized funding and permitting to install a wind sensor on Mt. Aeneas, and we are working towards funding a weather station on Tunnel Ridge in the Middle Fork. Stay tuned for these exciting improvements! If you are traveling outside of our region, MesoWest is the most comprehensive source for looking at weather stations.

Post #12 - 1/17/19

The Story So Far - A Mid-January Snowpack Review. By Blase Reardon, FAC Lead Forecaster.

It’s mid-January, and time for a review of the avalanche season so far. That can help us see patterns and alert us to upcoming problems. We’ll focus on upper elevations; at low elevations, the story is much simpler. Too warm! Too little snow! Too much bushwhacking!

Like any good story, this review won’t be comprehensive. We’ll leave some details out, like your buddy does when he has everybody laughing about that time that….. And like you wish your uncle would, when he goes on and on and on.

Chapter 1: In which the villain appears

October snow at upper elevations made for a promising start to the season. It was followed by some dramatic weather events and drier conditions. Among the dramatic weather was a warm, late October storm that brought rain to over 7,000 feet. The ensuing crust was buried November 2 by a storm that brought dense snow that bonded well to the crust. It also pushed the Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) at upper-elevation stations above average. So far, no villain.

Sadly, the pattern turned drier, which created weak layers at the snow surface. Snow buried this layer, followed by another warm storm that brought rain to about 5,700 feet. The mostly dry conditions prevailed until December 9, the end of this chapter. At that point, 7 to 10 inches of SWE had accumulated, and the snowpack at upper elevations had dropped to 80% of average.

The villain? There were several candidates. In areas with shallower snowpacks, like John F. Stevens Canyon, weak, faceted snow had formed near the ground. Sun crusts had formed on slopes exposed to direct sun, with facets developing around those crusts and the early-November rain crust. But was the weak snow that existed at the surface on Dec. 9 that would prove to the most fragile.

Chapter 2: The Plot Thickens (along with the snowpack)

The winter turned markedly wetter about December 10, and helped the snowpack close the gap on average. Over the next month, until about January 10, a series of storms swept through the forecast area. The storms dropped 7 to 13 inches of SWE in a series of storms and small snowfall events. The pattern favored the northern part of the forecast region, with Flattop Mountain SNOTEL picking up nearly twice as much SWE as Noisy Basin. The last storm of this period, which ended January 9th, brought rain to higher terrain, though the exact elevation varied from 5,600 feet (Whitefish Range) to 6,800 feet (Lake McDonald area).

The parade of storms didn’t allow for extended dry periods in which more weak layers could form near the surface of the snowpack. The primary avalanche problem during this chapter was initially storm slabs. These evolved into Persistent Slab avalanches failing on the weak layers formed during the season’s first chapter. In the Whitefish Range, a widespread cycle of natural avalanches ran with the first storm in December. Later cycles seemed concentrated in the Middle Fork corridor. And they seemed to grow in size with each storm, even as the number of observed slides diminished. People reported several crowns over a thousand feet wide. And around January 9, a very large avalanche ran near Essex; it swept over an alpine lake, left debris 10-15 feet deep, and likely failed on weak snow that was on the snow surface in early December.

Nonetheless, the avalanche danger was diminishing. By January 10, the fragile snow near the ground had strengthened except on upper-elevation slopes with thin snow cover. The December 9 interface had adjusted to the meter-thick slab consolidating above it. The villain was cornered in the highest, most alpine terrain.

Chapter 3: In which villain’s henchmen come out of the woodwork

While the previous chapters lasted one to two months, this chapter comprises just a week, January 11 to 17. Sometimes a short chapter is all it takes to set up trouble ahead. In this brief chapter, the dominant weather was high pressure that brought inversions to the region. For nearly a week, clouds seem to hand just above the valley floor. Above the clouds were blue skies.

Over this week-long period of stagnant weather, multiple weak layers developed at or near the surface of the snowpack. Facets developed in the soft snow above the rain crust left by the January 9 storm. The clouds provided a moisture source for a bathtub ring of surface hoar at mid and upper elevations. Where the air was drier, the low-density snow at the snow surface faceted. Clowns to the left of me, jokers to the right. And below. And above. Even Bruce Lee might be in trouble.

And that’s where we’re at on the morning of Thursday, January 17. Another chapter is starting. Snow is forecast for the next few days, and that snow will bury these weak layers. How they’ll react depends on the rate and amount of snowfall, but it’s pretty clear that in the next chapter, these layers will be our primary concern. Oh, and those basal weak layers may crawl out from under the bed and cause more trouble.

Post #11 - 12/3/18

When will it snow!?! An early season update on the FAC. By Zach Guy, FAC Director

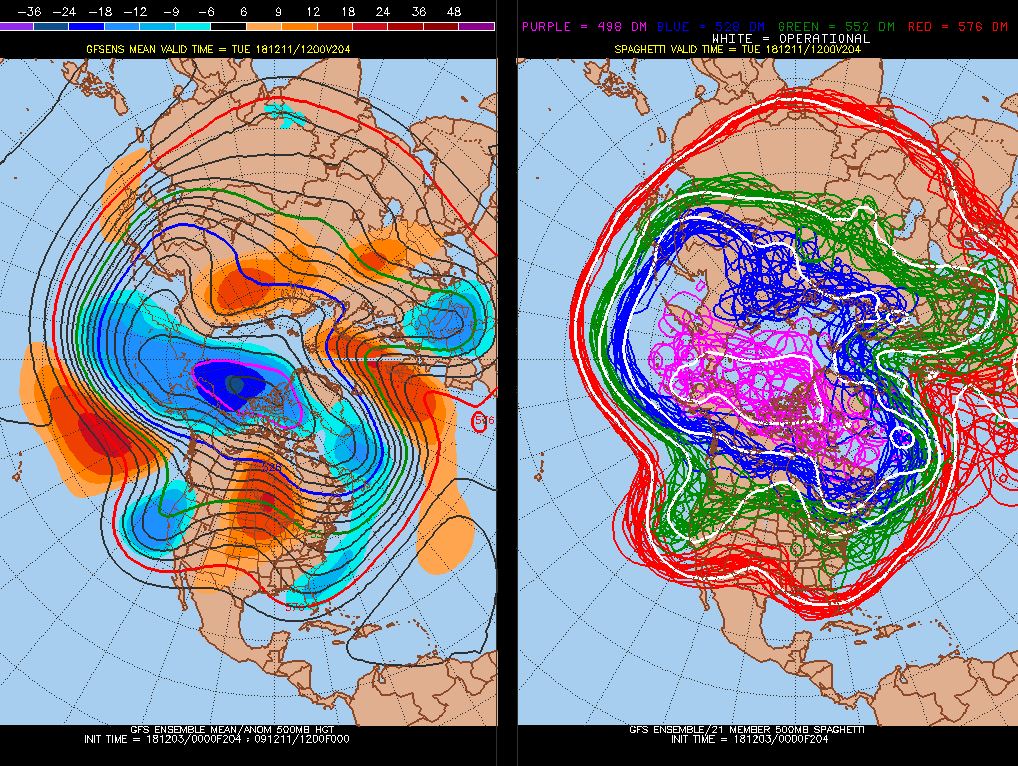

We are all on the edge of our seats waiting for a big storm...but unfortunately, it looks like another dry week ahead. A ridge of high pressure is moving onshore by Wednesday and will be parked over the Pacific NW for almost a week. These extended droughts can spell trouble for the snowpack. The clear skies and cold nights drive strong temperature gradients, especially when the snowpack is shallow and close to the warm ground. As we have already seen, facets grow larger and weaker with each day of clear weather. Surface hoar growth usually accompanies these high-pressure systems, making for an ugly "buffet" of weak layers. In many ways, our snowpack structure is shaping up to look a lot like last year's foundation, which resulted in a challenging persistent and deep persistent slab season and numerous major avalanche cycles. (See blog post #6 below). The key ingredient missing right now is a snow load.

Right now we are holding off on daily forecasts because the snowpack is thin and generally stable, with only small and isolated instabilities in high terrain. We will start issuing daily forecasts when the snowpack becomes more favorable for winter travel and when avalanche conditions become more dangerous. So when will it snow? Looking ahead at ensemble forecasts, we can see a trough developing over the Pacific Coast around December 10, and moving onshore over the next couple of days. We are still too far off to say anything with confidence yet, and often the models are overly optimistic about breaking down high-pressure ridges. However, NOAA's 8 to 14-day outlook shows above-average precipitation and temperatures, consistent with the warm and moist southwest flow at the leading edge of a Pacific trough. Our fingers are crossed!

The spaghetti string plot above shows an ensemble of GFS models for December 11. Although the placement and characteristics vary, most models agree on a deepening trough somewhere along the Pacific NW Coast, which is often associated with good precip for us. The graphic below shows NOAA's prediction of above-average precipitation for the Dec 11 to Dec 17 timeframe.

In the meantime, we're still paying close attention to the weather, publishing snowpack updates as needed, and tracking all of those weak layers that are forming during our dry early season weather. We have two new forecasters that I'm excited to have on the team: Clancy Nelson and Blase Reardon. I've had the opportunity to forecast with Blase in the Central Mountains of Colorado and I've been working with Clancy for a few weeks since he moved from the Sierra's, and I'm excited about the skill set and talent that both of these forecasters will bring to the center. You can read more about all of the staff on our bio page.

No other major changes to announce for the center this year, but here are a few updates. We are working through permitting and funding hurdles for a weather station in the Middle Fork and a wind station on Mt. Aeneas with the goal of having these in place by the fall of 2019. We are collaborating with a few other avalanche centers to develop a mobile app for getting forecasts, sharing observations, and more. We have an improved weather station map and table coming out shortly. You may also notice that we changed the "upper elevation" zone from >6,000' to >6,500'. We felt this better reflected the effects of increased wind and precip that often occurs in the alpine. We are making a few changes to our weather forecast tables to make them more digestible and useful for the public. We also updated our "How to Read The Forecast" page. Even if you are a regular visitor to the forecasts, you should take a look at this page because it defines what we mean by some of those vague terms like "possible" or "large" or "likely". Here's a huge preemptive thank you for all the volunteers, sponsors, FOFAC members, forecasters, and staff members who pour their time and energy into making our center what it is. We are ready for action...let it snow!

Zach Guy

Director, Flathead Avalanche Center

Post #10 - 4/10/18

Predictable Irrationality: A Series on the Human Factor. Part 3. Better Risk Mitigation Through Cheese. By Kelsey Bauer

If your personal backcountry goal is an awesome journey punctuated by a safe return home, then you’re probably more concerned with how to mitigate the last few heuristic traps discussed in this series than with their mechanics and origins. Really, no matter how much we blog and tweet and post about making good decisions, we’re still going to make human factor mistakes. May we present for your consideration: swiss cheese.

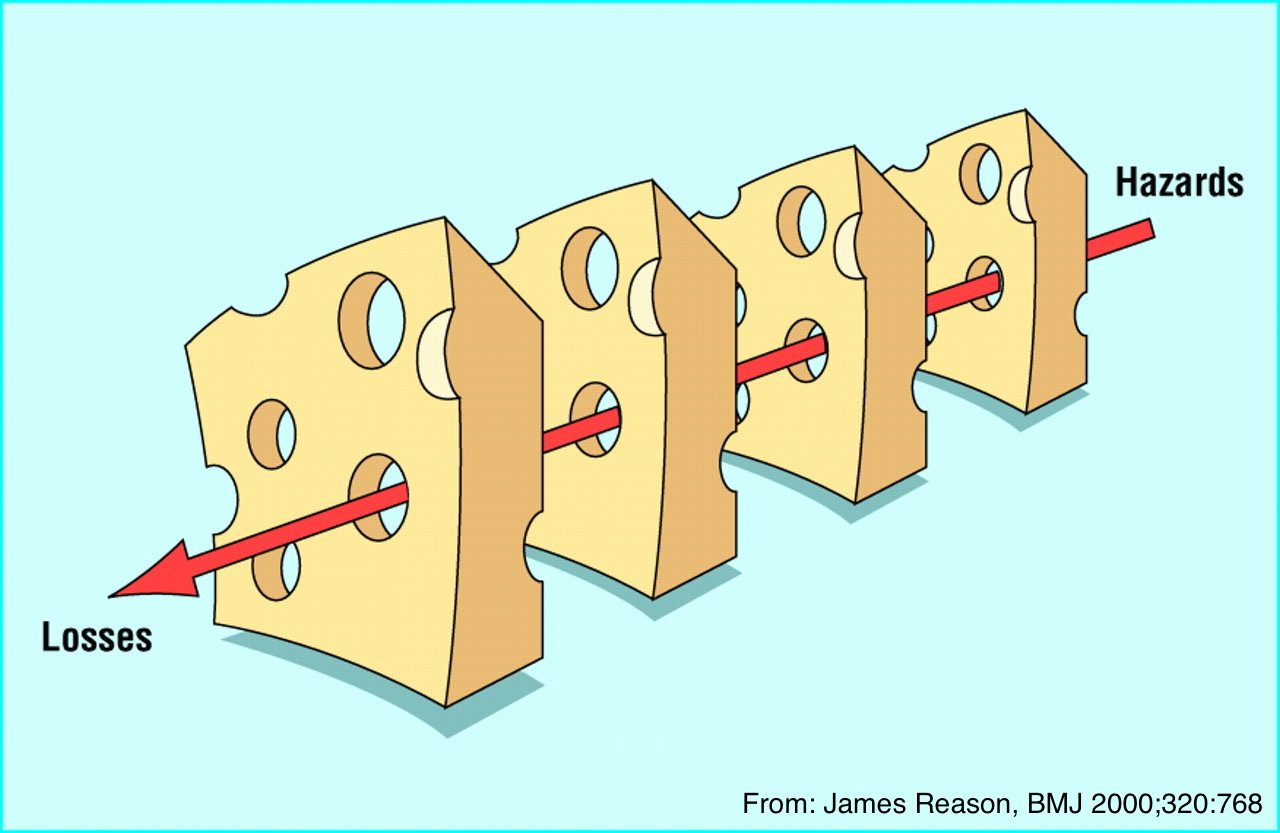

British psychologist James Reason uses the “Swiss Cheese” model as a systematic method for reducing negative outcomes that result from a series of human errors. Reason is mostly thinking about risk management in aviation and healthcare fields. He compares achieving a goal to a lineup of swiss cheese slices, with each slice representing a defense against an unwanted outcome, and with the holes representing all the ways our fallible human selves could go wrong. If too many holes, or errors, align amidst the cheese stack, the result will be an accident.

When applied to the concept of time in the backcountry, Reason’s cheese holes start to look a lot like the human hazards of terrain familiarity, peer pressure, confirmation bias, etc. Some of those holes can also represent factors outside your control, like snowpack and terrain features. The more slices you stack up, the less likely that a series of backcountry decisions and conditions will result in an accident. Your personal process might include different tactics, but here are a few cheesy suggestions to help develop a system of lactic defense for your backcountry outings.

Feel free to be selective about your group. When it comes to traveling in avy terrain, it’s wholly acceptable to have friends with whom you don’t ride or tour. Meet up with them afterward at the bar. Choose team members who practice with their safety equipment, who listen to input from the group, and who demonstrate their own systematic approach to decision making.

Leave your itinerary with someone reliable and plan to check in with them at the end of the day. Not only is this directly relevant to your safe return home, it checks and balances your thought process. If you feel squirrelly about leaving a route with your mom, you probably have no business traveling there.

Try not to overcommit, whether it’s to a route or a group. Feel free to excuse yourself from an invitation if your schedule’s packed or you’re low on steam for the week. Overextending yourself leads to lack of preparation and makes for more holes in the cheese. Besides, no one wants to be that twerp with a yard sale at the trailhead, looking for a fresh battery for their beacon.

Human failure is inevitable. Our irrational selves are going to let us down perennially. You don’t have to use the techniques suggested above, but go ahead and set up as many precautionary roadblocks as you need to protect yourself against your own irrationality. Even as we transition toward springier travel conditions, keep in mind that all of your defenses are still useful, and will continue to be relevant even after you stash your sleds or skis for the season. And when you’re packing that sandwich for the trail, don’t forget to lay the cheese on thick.

Post #9 - 3/19/18

Predictable Irrationality: A Series on the Human Factor. Part 2. The Portable Tribe. By Kelsey Bauer

Anyone with a grandmother knows the danger of watching all your friends jump off a bridge. They might convince you to jump too. Here in northwestern Montana, there are metaphorical bridges lurking in all our powder stashes if we rephrase the question. For instance, if everyone else skied off that rollover, would you do it too? If, according to the interwebs, Eric Peitzch skied Rescue Creek yesterday, should you do it too?

As social critters, we’re inherently susceptible to crowd-sourced wisdom, but this wisdom can really hamper our individual decision making in the backcountry. Reach back to your time in Avy 1 class and recall that the S in the FACETS stands for the proverbial bridge jumping decision. It’s “Social Facilitation” or what psychologists also call social proof.

When we see our friends high mark a slope, or watch someone ski an edgy line, we’re inclined to use social proof to justify our own participation in the fun. It’s our tendency to see an action as more appropriate when our neighbors are doing it. We’re tribal beings, and we take cues from those around us.

The A in FACETS is also at play here. Recall that “Acceptance” describes our tendency to seek validation from our crew. Rather than raise a dissenting opinion in our group and ostracize ourselves, our quest for acceptance makes us act in a way that ensures we’ll get invited along on the next trip. Simply put, it’s peer pressure.

In tandem, the combined influence of social proof and peer pressure has a powerful impact on our decision-making ability. It might, for instance, create an urge for us to drop right off the cornice with the rest of the powder lemmings.

As many experts have pointed out, social media amplifies both of these factors by allowing us to bring our whole tribe into the backcountry in the form of a smartphone. Instead of just seeking approval from our touring mates, we’re now looking for it from all of our online followers and friends. Social media outlets allow us to gather input from a broader crowd than the people in our immediate presence. We might be tempted to make our tour plans based photos of places and lines that everyone else posted recently (or even based on their snowpack observations on the FAC page!).

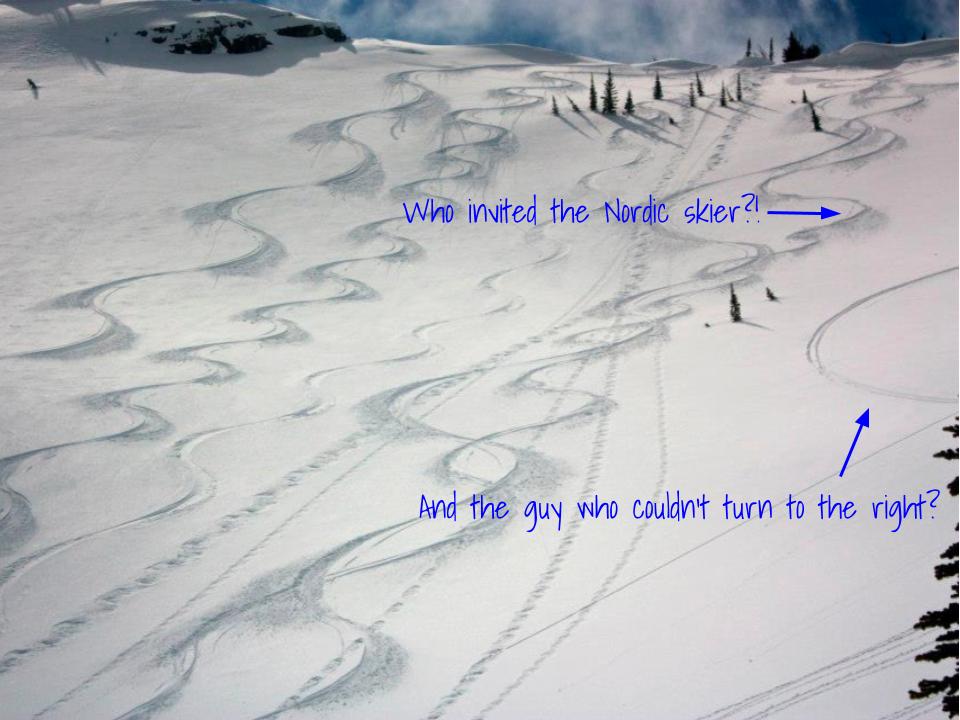

One member of our tribe shares the illustrative story of his time at a backcountry yurt a few springs ago. On the first day of the trip, his band of strangers proceeded to suss each other out and get to know the local snowpack by digging pits, acknowledging heuristic traps, and percolating out into subgroups. Although they observed a few layers of concern and signs of instability, our protagonist decided to attempt a back flip he’d been eying all afternoon. The light was just right for a photo and the crew’s attitude was lighthearted and playful. His landing impacted a layer of buried surface hoar and triggered the deep slab avalanche pictured above, out of which he was lucky enough to ski. The incident is a weighty example of just how much the extended sense of social proof and peer pressure can cloud our reasoning.

How are you going to combat your tribal instincts? Ideally, you might want to go out only with your friends who own flip phones, or with ancient telemark skiers who are impervious to the perils of social media. Pragmatically though, it’s best to fall back on a systematic process for decision making. Instead of making choices based on a whimsical social media post, rely more on your personal checklists and an evidence-based evaluation of the snowpack. Ask your group about their intentions for the day. Is that the safest line, or is it the one that would look great on your online profile? Make a practice of examining your motive every time you snap a pic.

It’s a dynamic atmosphere when we can consult with skier colleagues across our community in real time, whether by liking their posts, combing their snowpack observations, or just catching up in person at the coffee shop before heading out for the day. Here’s to all of you autonomous mavericks though, maintaining your tribal membership while you set your own skin track!

Editor's note: For another great read relating social media to avalanche accidents, check out this article. For Part 1 of the Human Factor Series, scroll on.

Post #8 - 3/4/18

Predictable Irrationality: A Series on the Human Factor. Part 1

Confirmation Bias: You Don’t Know What You Think You Know. By Kelsey Bauer

Who among us hasn’t been stuck at the dinner table with their proverbial Uncle Bill, circling around the same argument we have annually about the same hot-button topic, neither willing to budge in our unwavering opinions? No matter how much evidence we politely present to the other, we both head home unfazed. Psychologists have a painfully straightforward explanation for this charade, and it’s surprisingly relevant to the way we make decisions in the backcountry.

The expert term for our entrenched viewpoints is confirmation bias. It’s our tendency to interpret new information in favor of our already existing assumptions and to disregard input that might challenge those assumptions.

Confirmation bias is a mental shortcut that helps us make quick decisions in stressful situations. Processing information that’s contrary to our belief requires more energy than processing that which reinforces it. We’re wired to sift through excess noise and retain the stuff that supports our value set, while we chuck contradicting data to the curb.

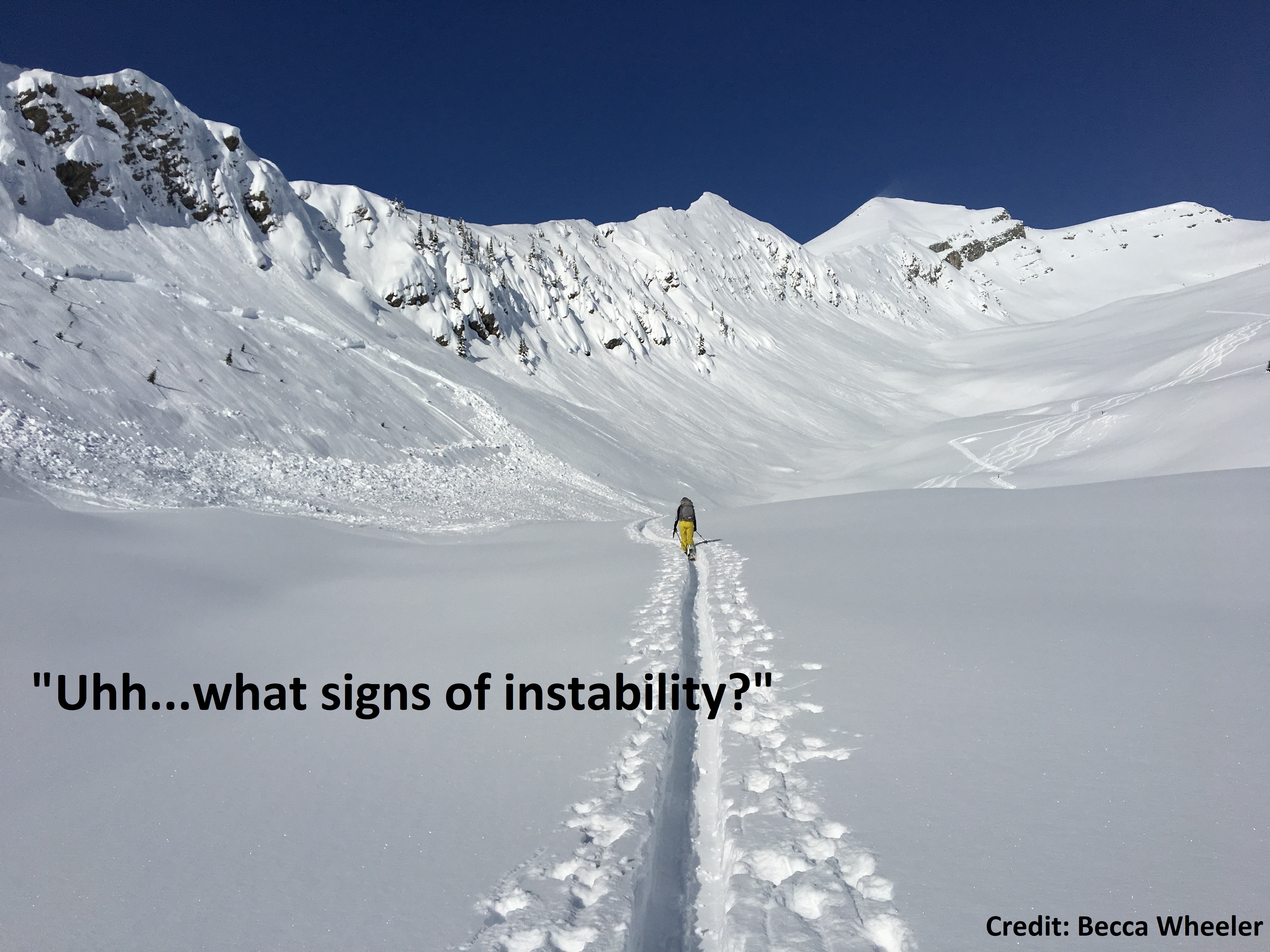

This proclivity might have served our prehistoric ancestors well in making quick and simple decisions, but it often works against our Gortex-clad pow-seeking selves. In order to critically evaluate the snowpack and make a safe call, we need to observe and process all the data, not just the bits that support our assumptions.

When it comes to avalanche safety, confirmation bias acts as an echo chamber effect. We affiliate with friends whose risk tolerance or aspirations for glory parallel our own. Our social media threads are full of posts that reinforce our quests for unadulterated powdery lines. After a great day ripping the canyon, we say things like, “All signs pointed to go,” instead of, “No signs pointed to no.”

Local psychologist Sara Boilen sums up the relationship between confirmation bias and risk assessment: “Our brains, in an effort to be efficient, use various shortcuts to quickly sort through incoming information. Unfortunately, this tendency makes us likely to miss tidbits or observations that could save our lives. If I check the avy report in the morning and see a Low or even Moderate rating, I am not as likely to expect to see signs of instability. I am then less likely to find those signs – even if they are literally underfoot.”

Luckily, there are plenty of techniques we can use in the field to counteract our powder-piggish traitor minds. Although it might sometimes feel like mental gymnastics, make yourself search for what you’re not expecting to see. Psychologists like to say, “Practice makes.” Not that practice makes perfect, but that by doing the thing, we do the thing. The more we practice combating our bias, the more we’ll do it reflexively.

Practice it while you scan the avalanche forecast. Are you reading “10-12 inches overnight,” or do you hone in on “storm slab instabilities?” Practice it in the skin track. Check in with your ski partners about their assumptions for the day and ask what the opposite of those assumptions might be. Practice it in your snowpit. Are you hoping for a few non-propagating ECTs to reinforce your plans to center-punch a sweet line, or are you looking for a reason to bail toward more conservative terrain choices? Instead of seeking data to confirm your hypotheses, try your darndest to disprove them.

If your group is feeling really nerdy, assign someone to be “devil’s advocate” for the day. Make it their job to disagree with everyone’s assessments. Not only will this help the designated contrarian examine their personal assumptions, it will also slow the momentum of the whole group’s confirmation bias.

Most importantly, call each other out. Don’t be afraid to compassionately ask your pals to state their case. Peer pressure can be our most powerful tool in mitigating our bias. We’re going to think more critically if we know our crew is holding us accountable.

Keep checking your confirmation bias throughout the ski season. Who knows? Maybe you’ll find you have a little more in common with Uncle Bill this year at Thanksgiving than you expected.

Post #7 - 2/10/18. Updated 2/22/18

Where are deep slabs failing? FAC Director Zach Guy

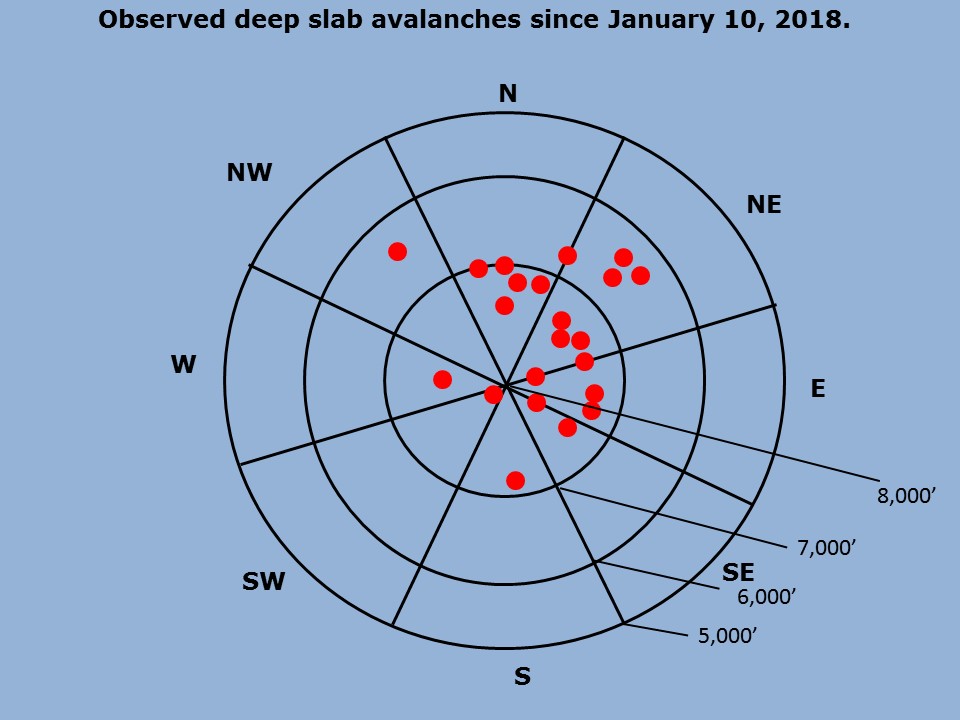

Deep slabs aren't a problem that we are used to dealing with every winter. Because they are so challenging to assess and have huge consequences, we spend a lot of time worrying about them. Here is a look at some of our data. I created a map of reported deep slab avalanches since we started describing the Thanksgiving Crust as a deep slab problem in our forecasts. You can click on each pin for photos of each slide. There are a lot of caveats with this data; Our samples are biased by the the places that we frequent the most or have better views of. That being said, there are some patterns worth considering. Deep slabs have been failing at upper elevations and more commonly on leeward or sheltered aspects. The Flathead Range has been most reactive, while the Swan Range has been the least reactive. The timing of naturals has been most commonly during warm and wet loading periods, especially the tail end. Take a photo and let us know if you see a deep slab. Our data is so limited that any bit helps. We'll periodically update this map as more observations come in.

**Note** This elevation rose is different than the one we use in our forecasts. I zoomed in on the mid and upper elevation bands to add additional detail. Note the three rings are 5,000', 6,000', and 7,000'.

Post #6 - 1/18/18

The evolution of our deep slab problem. Zach Guy, FAC Director

We use avalanche problems in our forecasts to help backcountry users identify avalanche concerns and make appropriate terrain choices. Avalanche problems were born from the idea that not all days are equal, even if the danger rating is the same. For instance, the danger might be rated Considerable and we anticipate numerous small natural avalanches that are easy to recognize and avoid. Another day, the danger might be Considerable and we are expecting only a few avalanches, but they will be very large and destructive. On those two very different days with the same danger rating, I will travel through the terrain differently and be on the lookout for different warning signs. This page has a great video about avalanche problems and describes the 9 problems that we use.

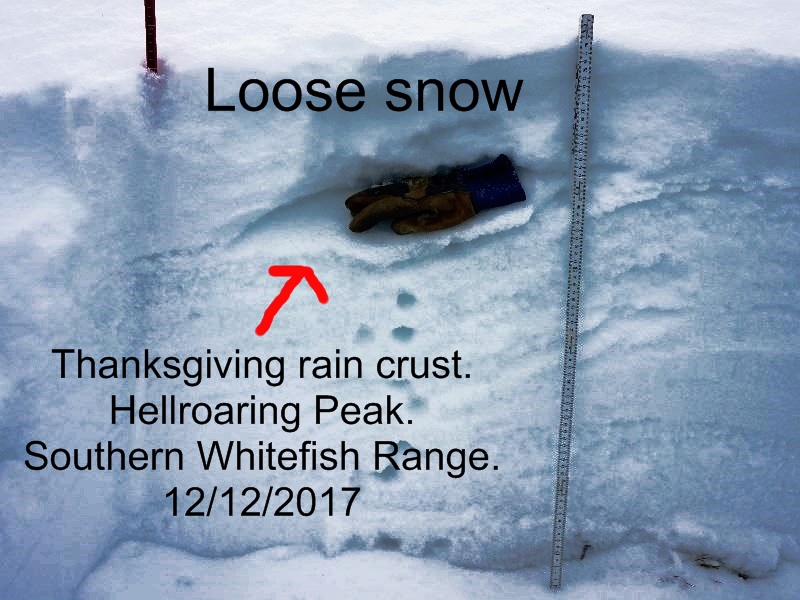

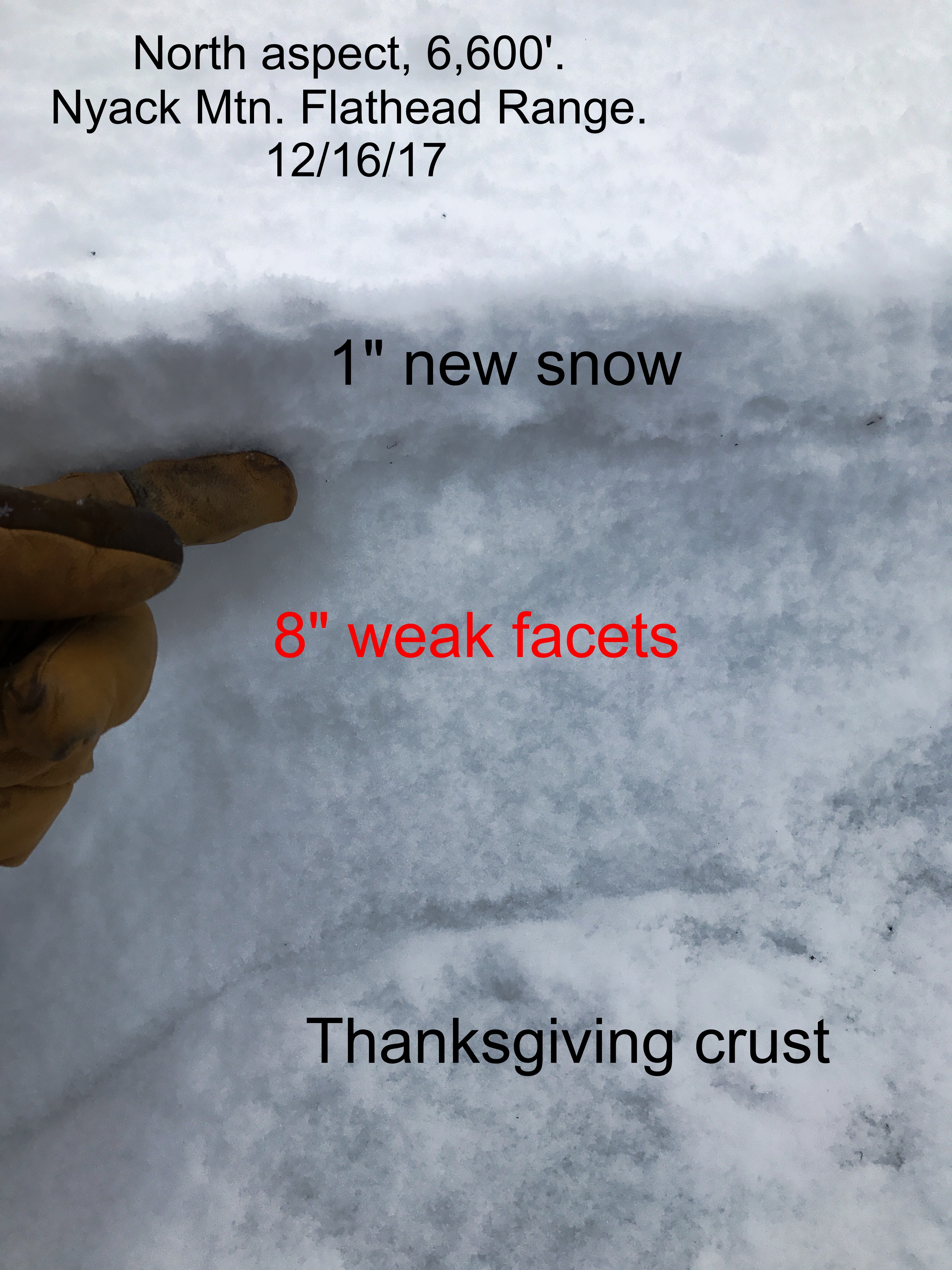

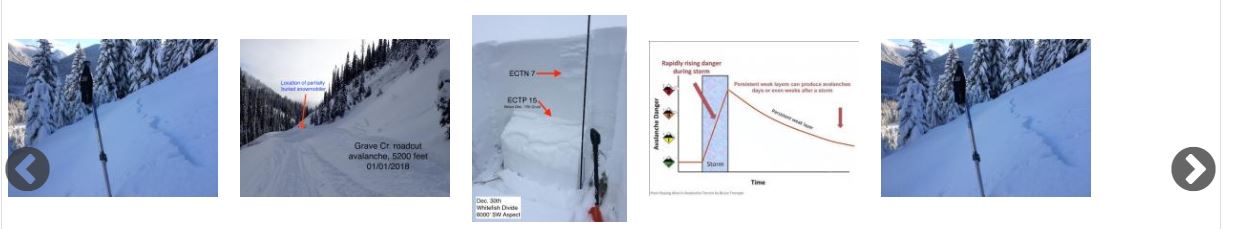

Oftentimes, there is overlap between problems, but we do our best to fit a variable snowpack into a few meaningful problems and travel advice in a way that is most useful and digestible for our users. This season has provided a rare and perfect example of the evolution of avalanche problems from a single weak layer that was born in December. This layer has become infamous and deadly across the entire Western U.S., and it has gained the nickname the DDL (December Dry Layer). Recall back to early December, when there was widespread despair over the lack of snow in our valley and across the West. It had rained extensively to the mountain tops here (leaving our Thanksgiving Crust), and snowed just enough to leave some low density snow on that crust or on the ground. That snow quickly rotted away during the subsequent weeks of cold, dry weather as we all started burning our snow gear or performing weird snow dances to appease Ullr. The avalanche danger was low and we were only concerned about small, loose snow avalanches entraining this weak and cohesionless layer. I'll provide a time lapse of photos from the Whitefish Range (on the left side) and the Flathead Range (on the right side) to highlight the evolution of the DDL.

Before burial: D1 Loose snow avalanche concern

During first storm: D1 to D2.5 Storm Slab

Our first storm produced a very widespread cycle on these weak layers. More so in areas that saw more snow. It was a classic storm slab instability that was easy to predict and recognize. We saw heavy snowfall, plenty of signs of instability like shooting cracks or other avalanches. The slabs were soft, relatively shallow and generally behaved in predictable manner. We could easily gather evidence from small test slopes, shear tests, etc.

2nd Storm: D2 to D3 Persisent Slab

The next storm came in quickly and resulted in another round of widespread avalanching. However, the rapid load seemed to mostly shed off in the new snow layers, and we didn't observe nearly as many slides breaking on the DDL. By this time, we were calling failures on the DDL persistent slabs: the weak layer was persisting under a thicker and more cohesive slab now, and it was producing larger avalanches, up to D3 in bigger terrain. It didn't produce widespread signs of instability like the first storm, but we would get occasional feedback. Some collapses and shooting cracks, or propagating results in stability tests, which all began to wane in the week after the storm. There were some slopes that didn't have the right ingredients (the slabs had flushed, the weak layer wasn't there, or both), and these were the safest slopes to go to if we wanted to ski or ride in steep terrain to allow a buffer for the trickier and less predictable behavior. Areas with deeper snowpacks were healing quicker, such as the Swan Range.

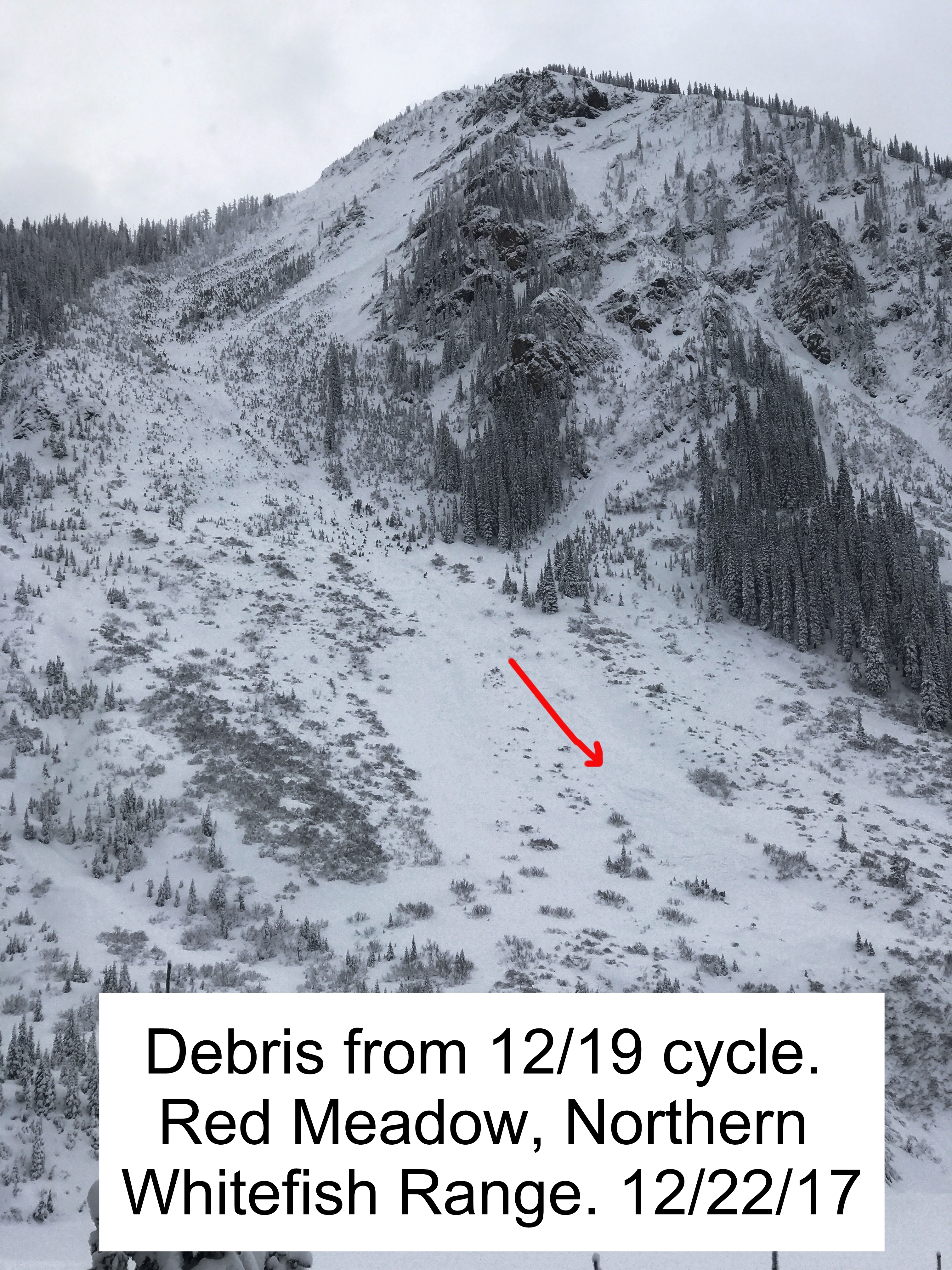

Our last storm: Shifting to D3 to D4 Deep Slab concern

During our last storm cycle which ended last weekend, the problem grew even larger, and evidence became hard to find. We went an entire week of continued snowfall with very limited feedback (no large avalanches reported, one collapse observed, and mixed results from stability tests which were pointing more and more towards improved stability). When the storm cleared, we set eyes on 8 avalanches that broke down to this layer (and there were undoubtedly more). Although we didn't see widespread activity, the sizes were even larger, from D3 to D4, and we measured one crown to be at least 7 feet deep. These slides were easily large enough to destroy vehicles. This cycle peaked during a very rapid and warm loading event at the tail of the storm. We are now in the deep slab phase. Signs of instability will be rare or nonexistent. Spatial variability of the DDL is challenging and the reliability of single point assessments on deeply buried weak layers is highly unreliable. We may go days (or weeks?) without any avalanches on the this layer, and then whammo...we will see something go in a very big and destructive way. Or maybe we won't. Deep slabs are fickle and the single most challenging problem for forecasters and recreators alike, because they give such poor feedback but carry such dire consequences. Our best strategies for these beasts is to avoid the terrain that makes us worried. In this case, our data suggests the problem has shifted to higher terrain. Deep slabs tend to occur during big warmups and big loading events, so use extra caution, even in runout zones, during volatile weather. However, they can be human triggered well after the storm is over. Staying away from shallow points and rocky areas helps improves your odds, but these trigger points can be concealed and impossible to see before the avalanche pulls out and reveals them. Of course we have more problems on the list now, such as a surface hoar/ faceted rain crust that was buried a few weeks ago (our newest generation of persistent slab), and now another layer of crusts and surface hoar buried today (our newest generation of storm slabs) We may phase out deep slab problems during periods of benign weather or if other problems are significantly more active and threatening. That being said, it will be hard to rule this problem out completely and there will always be some forecaster uncertainty around it because it is such a challenging problem to assess.

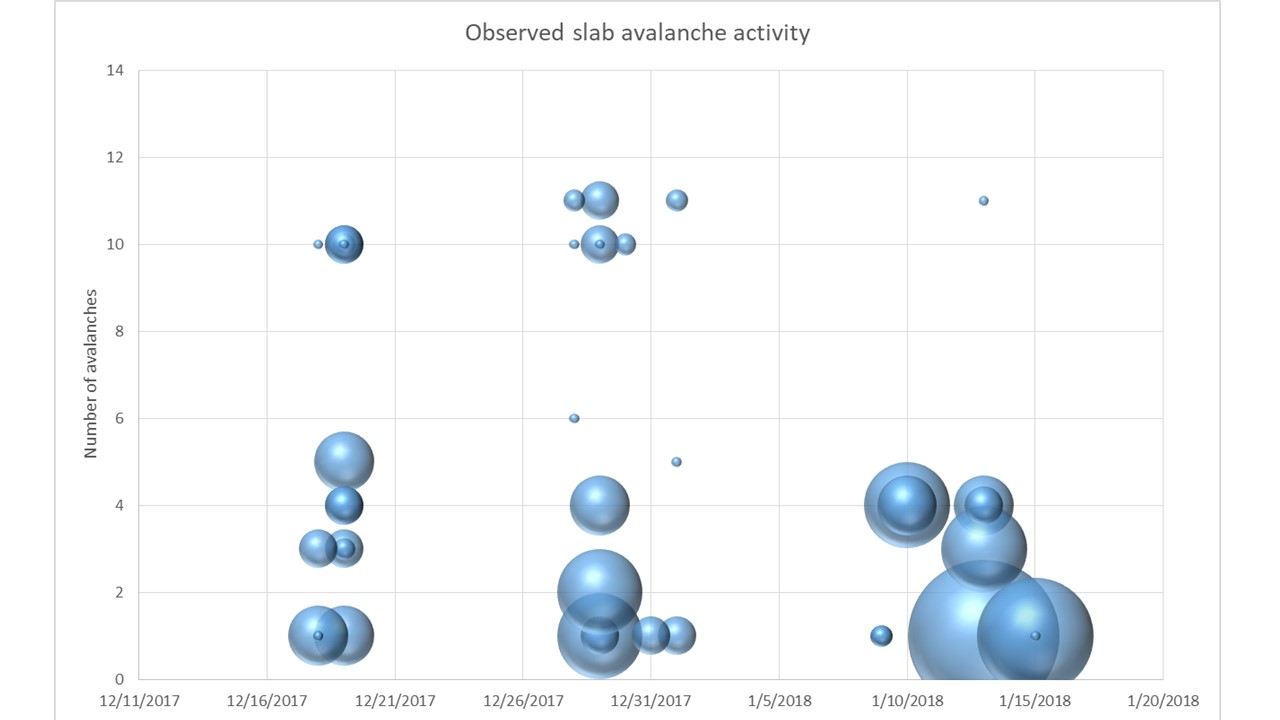

The graph below depicts all of the slab avalanche activity recorded in our database from this season since the DDL was buried. The size of the bubble demonstrates the destructive size of the avalanche (the smallest=D1, the largest=D4), while the vertical axis shows the number of avalanches for that given size on a given day. You can see a higher frequency but smaller avalanches from the first two cycles, and fewer but far more destructive avalanches from the last cycle. Remarkably, there have been very few avalanches triggered during the weather lulls between avalanche cycles. This is not commonly the case for persistent weak layers (and hasn't been the case for Canada or other areas in the Western U.S.) I think this speaks volumes to the patience and smart terrain choices of our backcountry users here.

Post #5 - 1/8/18

A few changes to the website. Zach Guy, FAC Director

The dust is finally settling from our last two significant storms and avalanche cycles, and I’ve been wanting to highlight and explain a few changes to our website this year. We made these changes in an effort to improve our products for the wide range of users in this valley.

1) New observation platform.

We have a multi-tiered observation form to encourage quick summaries as well as more thorough observations. Your observations are essential to our forecasts, so we want to make the process as painless as possible. The “Quick Observation” tab just asks for your contact info, location, and a a quick text summary, with the option to upload photos or videos. There are additional tabs for our those of us who want to add specific details on our route, snowpack, weather, or avalanche observations. Hopefully this multi-tiered is easier to digest for all of our audiences and will encourage more public observations to help with the accuracy of our products. You can always email us, or call/text us 406-66AvyOb too.

2) Supplemental media for avalanche problems

On the forecast pages, we have added a slide show below each avalanche problem that is intended to help further your understanding of the problem. Our forecasters choose the most relevant photos each morning. They may not be chronological or recent photos, but rather, the best photos to demonstrate what the avalanche problem might look like or how to identify it in the field.

3) Consolidating the recent observations and current weather conditions into the discussion

Our job as forecasters is to synthesize a large amount of data from observations, weather stations, and weather forecasts into a product that you can understand, retain, and use to make educated decisions in the backcountry. To prevent information overload, we removed the “Recent Observations” and “Current Conditions” tables from the forecast page. Instead, we are highlighting the most relevant and critical observations into our technical discussion and problem description. For instance, if we receive 5 new observations with all sorts of pit data, we will do our best to summarize what is most relevant to the day’s problems and provide hyperlinks to essential observations or photos. If new snowfall is a key player in today's problems, we will highlight where and how much snow fell. All of this observational data is still available on our website through our observations page and weather station map and table, and we encourage you to gather this supplemental information before heading out.

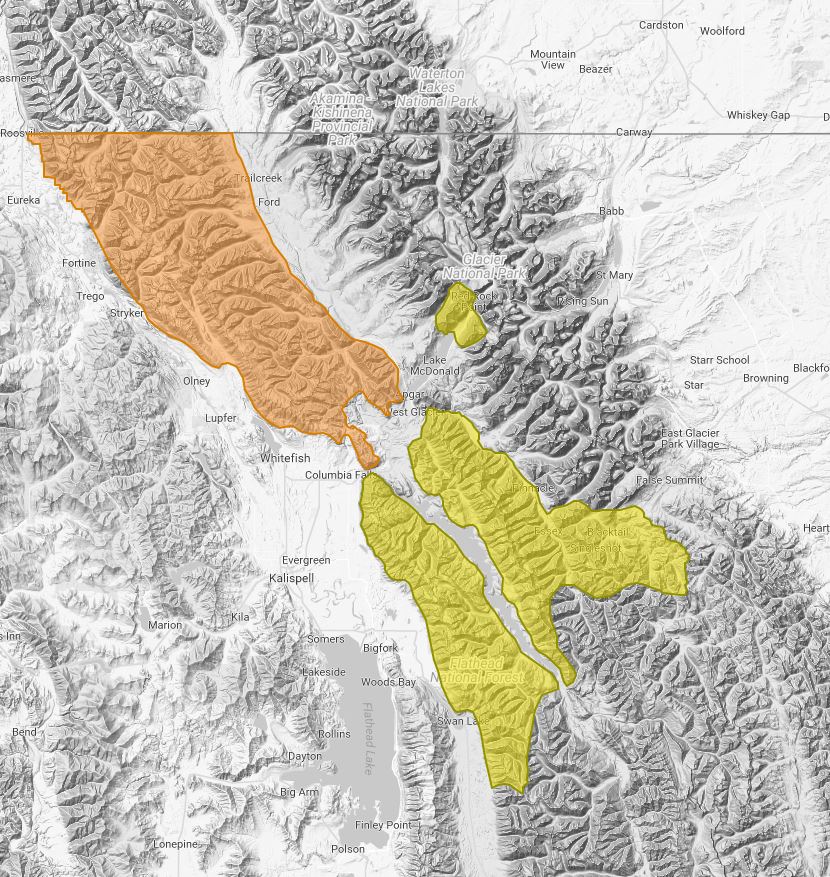

4) Differences between forecast zones

As our snowpack evolves, we may highlight significant differences between the different mountain ranges by publishing separate forecasts for each mountain range. In general, our technical snowpack discussion will be the same across all ranges, but the danger rating and avalanche problems (avalanche character, size, likelihood, and distribution) may be different. We want to provide as accurate and useful information as possible within the scope of our resources. Make sure you check the avalanche forecast for the area that you plan to recreate, and know that there may be differences between the 3 mountain ranges. Our email subscribers will receive separate emails for each mountain range on those days that we publish separate forecasts.